Wine lovers are not part of an elite. Not every car driver needs to own a Rolls Royce or a Lamborghini, and not every resident needs to inhabit a roof-top apartment or a cliff-top mansion. Similarly, not every wine-drinker needs to consume an exclusive vintage. These are all status symbols for the rich.

Too much of the wine literature focuses on “the best” (intended for “true wine lovers”), not simply the above-average (The price of exclusivity: how wine lost its everyday appeal). Wine is often made into the star, a thing that people need to revere (“wine speaks to us”), rather than being created simply for pleasure. So, wine is not an elitist pursuit (not status), nor is it an unhealthy one – in both cases provided it is conducted in moderation.

Good wines are not inaccessible to my peers, provided we know where to look for them. The returns will re-pay even a small amount of effort. All we need is that the bottle contents should match the price, and choosing the latter thus chooses the former — the younger people need to be told this, and especially this. Even cheap wine can be interesting, depending on its origin; however, quality does cost money, and must be paid for.

So, now seems like a good time to look at some market trends in the United States wine industry. In the past, consumers have traditionally gone through their 20s into their 30s, and then they have naturally transitioned to wine — this doesn’t seem to be happening now. Mind you, it is repeatedly said that the modern trend is to drink less but drink better.

That said, we could start with the change in average bottle price 2013–2024, as shown above (from: Sovos ShipCompliant and WineBusiness Analytics 2025):

In 2024, the average price per bottled shipped increased by 6% to a record $51.20. The continued slowdown in the rate of price increases, which declined from 7% in 2023, 9% in 2022 and 12% in 2021, reflects a broader easing of inflation. However, this increase remains well above the pre-pandemic average annual change — we are told that this is preferentially because the volume of sales of cheaper wines is now declining, rather than the more expensive wines are increasing (2024 Beverage Alcohol Year in Review).

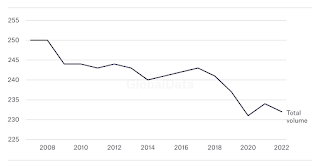

That said, we can also look at the sales growth of premium wineries 2000–2024, as shown above (from: Silicon Valley Bank State of the US Wine Industry Report 2025). This shows a distinct downwards trend, indicating that even the expensive wines are selling much worse, through time. There have been, however, two distinct dips and one peak.

What we have is an obvious set of evolving social norms (What if we didn't turn into our parents?), and a growing focus on health and wellness, rather than on the fanciness of the wine itself. We can see this by looking at various parts of this report: Colangelo Partners U.S. Wine Market Trends and Challenges. I will do this now.

We can start by looking at what people think about wine’s effect on their health and well-being, for the different age groups, as shown above. Wine is seen to have a notable effect for all groups, but it is the oldies (my group!) who detect the biggest effect, especially on their well-being.

Looking in more detail, we can see what these effects are thought to be, as shown above, for the three groups. Apparently wine is not really part of a healthy diet, although it has been historically important, and it does go with food (wine is always best consumed with food, otherwise you risk becoming an alcoholic). The older people are apparently much more amenable to wine consumption.

In terms of actions, the younger people do express their intent to participate in Dry January, and have done so in the past, as shown above. The older groups are much less keen (and I would definitely fit into my oldest age group). By comparison, apparently 55% of a survey of French consumers declared a willingness to abstain from alcohol in January, but ultimately only 18% declared that they had succeeded (The growth of NOLO in France). There are, of course, good reasons for not drying out your January (Yes, you can drink without guilt).

More seriously, some people have taken the recent WHO guidelines earnestly, as shown above, especially among the younger people. We older people, of course, do not (Harvard researchers and leading statistician stand up to the WHO), and things are not so simple (The complex case of moderate drinking). However, as Louis Pasteur famously noted: “Wine is the most healthful and most hygienic of beverages.”

Finally, it is worth noting other risky behavior apparently carried out, for the various age groups, as shown in the table above. It seems to me, given this, that wine is the least of their likely health problems. Eating junk food cannot be good for you; and coming from Australia, as I do, we know to put on sunscreen, or at least wear a hat (the sun is a bigger cancer risk than either red or white wine: Red vs. white wine: New study finds little difference in overall cancer risk).

Anyway, that is what some of the opinions in the wine market in the USA look like just now. Interest in wine is declining (Wine sales slipping in US as more Americans leave alcohol behind); and at the entry level, quality wines are disappearing (The cost of premiumisation). Younger people have also been starting to look more closely at ready-to-drink (RTD) concoctions based on wine (The wine-based RTDs we are too embarrassed to talk about).

We have also apparently been failing to communicate that we enjoy wine (Rediscovering the fun in wine), except perhaps through the non-educators on TikTok or Instagram (The role of wine influencers). Instead of Dry January, we have Come Over October and Share & Pair Sundays. Or, as the French campaign of 1933 noted: “Drink wine, live joyfully”. Moreover: Wine industry leaders look on the bright side; and indeed the 2024 California Grape Crush Report shows the lightest crop in 20 years, which will help address the current over-supply of U.S. wine.

Given all of this, we have apparently been making too much wine for quite some time, but we have only recently woken up to this idea (The 2025 wine industry wake-up call). We need to either reduce vineyard area or create wine demand (eg. Young adults find restaurant wine lists uninspiring). Not only do younger people tend to drink less than older ones, they lean toward lighter wines, they buy less for status and more for taste, and they are more open to new products (Year of the Snake bites for China wine).

We could perhaps take a hint from the Champagne houses, which have focused on making and offering products that their target consumers will enjoy and want to buy again, rather than trying to educate consumers about wine as a complicated accompaniment to food (Robert Joseph). That is, we need to see the importance of embracing curiosity and telling the story of wine (Alecia Moore: Pink). We also need to refocus from the concept of physical health to one of emotional wellness — from wine we get flavor, enjoyment, culture (With its health halo dimmed, wine needs new ways to win over drinkers). Hint: make consumers smile and they are more likely to engage with your brand (Tim Akin). All of these points were emphasized and amplified at the recent Unified Wine and Grape Symposium (Stressed and worried, young people need wine).

So, as a finish, this might also be “an opportune time to talk to buyers and experts about what they think wine, and wine enjoyment, might look like in the next 50 years” (The future of wine: what might the next 50 years have in store?). Presumably, given the interest shown above in diets, one of the most obvious innovations will be ingredient and nutrition labels for wine, as in the European Union (Notes of...fish bladder?!) and increasingly in the USA (Wineries promote transparency by adding ingredients lists). More seriously, some countries either already have cancer warnings or are considering them (Should Australia mandate cancer warnings for alcoholic drinks?).