I thought that it might be interesting to gather together references to publications that refute these claims, or at least suggest that they are exaggerated; and that is what I have done here and in the next post.

At first, I will start by pointing out that a reply to the above publication was published in The Lancet a couple of months later (Alcohol and health: all, none, or somewhere in-between?):

The risks and harms associated with alcohol are well documented, and the substantial harms of heavy or binge drinking are not debated. But health benefits of lower levels of alcohol intake have been widely reported. Many studies have shown that low or moderate amounts of alcohol (particularly red wine) can reduce risk for cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and even death — possibly due in part to a tendency to reduce systemic inflammatory mediators. These benefits might be limited to adults older than 40 years ... Potential benefits of light to moderate alcohol consumption have also been reported among patients with rheumatoid arthritis.

Dire warnings like these seem to have become commonplace (a similar statement about alcohol and cancer was issued by the American Society of Clinical Oncology in 2017) and have the potential to be ignored by many people as undesirable and unattainable. WHO correctly argues that no studies have addressed whether the potential benefits of alcohol on cardiovascular disease and diabetes outweigh the risks with regard to cancer, and that the harms of alcohol fall disproportionately on disadvantaged and vulnerable populations. In view of these truths, a why-risk-it approach might seem sensible. But interpretation of the seemingly conflicting reports requires consideration of many factors, including the varying levels of alcohol intake considered light to moderate, competing risk factors for disease, choice of comparator groups, and the known pitfalls of self-reported alcohol consumption. It is also important to put the results of these studies in the context of absolute levels of risk (versus relative risk) associated with alcohol intake, which are generally quite small.

So, even at the time, the WHO’s pronouncement was questioned, because it focused on cancer rather than any other health characteristics (of which there are many!). And, of course, alcoholism itself is not good for you, by definition.

However, organizations that advocate for more stringent policies around the sale and marketing of alcohol are gaining momentum (What do neo-prohibitionists really want?). In fact, it has been suggested that the influence is entering US politics (Source says Feds will declare “no amount of alcohol” is healthy). So, we need to take this seriously.

Now we might look at some other publications, that review the topic. These also refer to things other than cancer, and in particular they focus on wine as opposed to other forms of alcohol. I will look at an overview paper here, and then continue next week with some more details.

We should start with defining low (1–7 drinks/week) and moderate (8–21 drinks/week) wine drinkers, as designated in the best of the recent review articles (Moderate wine consumption and health: A narrative review). These researchers note:

Although it is clearly established that the abuse of alcohol is seriously harmful to health, much epidemiological and clinical evidence seem to underline the protective role of moderate quantities of alcohol and in particular of wine on health. This narrative review aims to re-evaluate the relationship between the type and dose of alcoholic drink and reduced or increased risk of various diseases, in the light of the most current scientific evidence. In particular, in vitro studies on the modulation of biochemical pathways and gene expression of wine bioactive components were evaluated. Twenty-four studies were selected after PubMed, Scopus and Google Scholar searches for the evaluation of moderate alcohol/wine consumption and health effects: eight studies concerned cardiovascular diseases, three concerned type 2 diabetes, four concerned neurodegenerative diseases, five concerned cancer and four were related to longevity. A brief discussion on viticultural and enological practices potentially affecting the content of bioactive components in wine is included. The analysis clearly indicates that wine differs from other alcoholic beverages and its moderate consumption not only does not increase the risk of chronic degenerative diseases but is also associated with health benefits particularly when included in a Mediterranean diet model. Obviously, every effort must be made to promote behavioral education to prevent abuse, especially among young people.So, wine is not the same as other forms of alcohol. If you want to get technical: “the beneficial effects of wine are mostly derived from its polyphenolic content, and this represents the crucial difference between wine and other alcoholic beverages.”

We also need to get clear what we mean by “a drink”. We might try this definition (Why do medical experts define moderate drinking as one to two glasses of wine per day?):

In the United States, the Departments of Agriculture (USDA) and Health and Human Services (HHS) recommend that men consume no more than two alcoholic beverages per day, and that women consume no more than one. Those U.S. Dietary Guidelines issued by the federal government also serve as guidelines for medical professionals when they define moderate drinking.

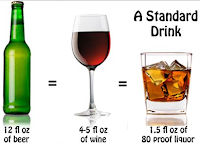

However, exactly how much alcohol constitutes one “drink” varies from country to country, as do dietary guidelines. In the U.S., one “drink” is defined as containing 14 grams (0.6 fluid ounces) of pure alcohol, which equates to 12 ounces of beer (5 percent alcohol by volume), 5 ounces of wine (12 percent ABV) or 1.5 ounces of 80-proof distilled spirits (40 percent).In Europe, a standard glass is often taken to contain 12 grams of alcohol, instead. This is: 50 cl standard beer, 33 cl strong beer, 12 cl wine, 4 cl of liquor (Dags för “alkoholfri operation“ [in Swedish]). By risky use of alcohol these scientists then mean: >14 standard glasses / week for men and ≥5 standard glasses at one time for men, and >9 standard glasses / week for women and ≥4 standard glasses at one time for women. This Swedish paper then discusses how much you should reduce these before hospital operations.

That might be enough science for one week. Next week I will look some more at where those glasses can safely go, according to research.

No comments:

Post a Comment