Historically, Europe has had three classes of land-users. At the so-called top have been the nobility, who owned lots of land but hired people to look after it for them — they had no role in the actual running of their farms. Next down the hierarchy have been the landed gentry. They lived in fancy large houses, and still hired workers to look after things, but they did also involve themselves in the running of their farms (that provided their wealth). Down at the very bottom of the heap were tenant farmers, who worked the land themselves, by hand, but did not actually own it — they had to give part of the produce to the landowner, as rent.

These days, the remnants of this system are still widespread in Europe, even though modern farms are mostly owned by neither the nobility nor the landed gentry, but by the proletariat. (NB. The wineries themselves may be owned by large companies.) For example, my house here in Sweden is surrounded by the remnants of the old feudal system. If I go for walks through the old farmland (and forests), I will frequently pass the tiny shacks in which the tenant farmers lived, next to the tiny fields that they worked manually. This is nothing like going for a similar walk in the USA or Australia. (None of the Longest straight roads in the world are in Europe, either.)

Needless to say, the European Union (EU) keeps a detailed numerical tab on the current situation of its farmland; and the survey data for 2020 are accessible in their online database (Eurostat). Unfortunately, only EU member states having a minimum planted area of 500 hectares are included in the data collection for any given crop. So, we cannot look at the vineyards of Sweden, for example, since there are only c. 100 ha of them (250 acres), in total.

However, there are data for the vineyard areas of 26 of the EU countries; and these are shown in the graph. (Note: there are currently 10 other EU countries.) Each point represents one country (some of which are labeled), located horizontally based on its total national vineyard area (ha) and vertically based on the number of actual vineyard people/companies who are recorded as owning that land.

The pink line represents the situation where every vineyard is 1 ha in size (2.5 acres), on average. So, countries above the line have an average vineyard holding of <1 ha each, while countries below the line have a larger average. The two unlabeled countries near the line are: Czechia and Bulgaria. The EU average vineyard holding size is 1.4 ha (3.5 acres).

As expected, being the biggest producers, Spain, France and Italy have by far the largest total vineyard area. However, their average vineyard sizes are quite different, with those of France (10.6 ha) being much larger than either Italy (2.3 ha) or Spain (1.9 ha). It is likely that the bigger French figure is influenced by the history of large Medieval monasteries and châteaux that were the foundations of modern French wine-making (The evolution of wine — and its buildings — in France).

By non-European standards many of these vineyards are very small, and often not commercially viable. In part, this represents all of the family holdings of a dozen rows of vines, originally used for home wine-making or for eating. In the old days, one produced one’s own food, rather than visiting a shop; and many people still live like this, at least partially.

Note that Luxembourg has the next largest average holding (4.6 ha), after France. Many of you may not even know exactly where this small country is, let alone that it produces wine. However, the quality of wine is deemed high (The wines of tiny Luxembourg make a big impression), but about two-thirds of it is consumed within the country itself. It mostly consists of aromatic whites and Pinot Blanc.

Following Luxembourg, we have Austria (av. 3.8 ha), Slovakia (3.0 ha), Germany (3.0 ha), Hungary (2.4 ha), Portugal (1.5 ha), Bulgaria (1.4 ha), and Czechia (1.1 ha). It is important to note that we are not talking here about the number of wineries, but the size of individual vineyard holdings. For most owners (ie. grape-growers, not wine-makers), their grapes are sent to a local co-operative for vinification, or sold to a local commercial winery. Co-operative wineries are much less important in the New World.

After this, come the truly old-world vineyards, as described above. These include Cyprus (av. 0.6 ha), Slovenia (0.5 ha), Greece (0.5 ha), Croatia (0.5 ha), and Romania (0.2 ha — this is smaller than the block of land on which my house stands). Romania, for example, has 844,015 recorded holdings for its 180,683 hectares of vineyards, nationally; and Greece has 193,284 holdings for its 103,058 ha. Even the smallish island of Cyprus has 13,740 holdings for 7,613 ha of vineyards. In these places, the resulting wine is often quite generic, since it is produced by the large co-operatives. *

How the European Union keeps track of all of this information is not clear!

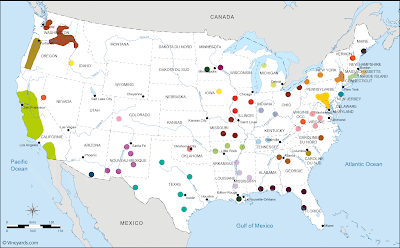

Anyway, I have the data to compare this situation to a few states of the USA in 2017 (see How has the vineyard area of the US states changed over the past century?). The top six states by total vineyard area (in order) each have average individual holdings of:

- California (29.9 ha),

- Washington (22.0 ha)

- New York (10.8 ha)

- Oregon (5.9 ha)

- Pennsylvania (8.5 ha)

- Michigan (6.3 ha).

As another comparison, we can compare these vineyards sizes to the number of wineries themselves. Based on the number of wineries per state in 2021 (Statista), these are the average vineyard areas used per winery:

- California (74.0 ha)

- Washington (35.2 ha)

- New York (29.4 ha)

- Oregon (10.3 ha)

- Pennsylvania (14.4 ha)

- Michigan (22.2 ha)

So, that is the difference between the Old World vineyards and the New World ones — the continents are not different just in the taste of the wines they produce. History still matters, along with terroir and technology. This situation arose when Europeans finally adopted the practices of the Agricultural Revolution, where the people of the Middle East invented farms, instead of being hunters and gatherers. The New World situation arose during the Industrial Revolution, when mechanization allowed farms to become much bigger. ***

Let’s face it European vines are grafted onto native American rootstocks (to deal with phylloxera); so the Europeans have to maintain something of their own! And of course, US viticulture was originally established on European principles in the eastern states (This 60-year-old winery changed the way America grew grapes), and Spanish missionaries further west (California's OG wine grape might be its modern day savior).

* Note that Wine Enthusiast is no longer enthusiastic about tasting wines from Bulgaria, Croatia, Luxembourg, Romania, or Slovenia, along with a bunch of other countries; and even many US states, including Michigan and Pennsylvania.

** It is also worth noting that in many parts of the New World the Covid-19 pandemic has created problems for grape-growers, especially at harvest time (eg. Situation critical for some growers with farm labor missing in action). In this situation, the smaller your vineyard is, then the less of a problem you are likely to have (because you can do the work yourself).

*** This is also when global climate change was initiated, although it took another century and a half for humans to notice its effects. Things often work very slowly in this world, no matter how much modern people try to rush.