Things like global climate change (the negative effects of which substantially outweigh the positives), biodynamic agriculture, regenerative viticulture, sustainable winemaking, and worldwide over-supply are all undoubtedly big issues in the wine industry, and they rightly occupy a large amount of space in the wine-industry media. However, there is one issue that far exceeds all others — not many people want to drink wine any more. These other issues cannot be addressed properly until the latter one is addressed first; and so I will discuss it here.

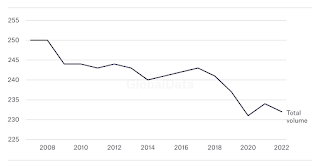

The above graph shows recent world wine consumption (mhl) since 2007, as released by the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV). It is not a pretty sight.

There seem to be two issues that combine to create this disaster:

- declining consumption of alcohol among younger drinkers

- declining consumption of wine relative to other forms of alcohol, especially cheaper wines.

One of the basic consequences of this issue is, of course, that global wine production always exceeds consumption, as I have written about before:

When will world wine consumption finally catch up with production?

Why does world wine production always exceed consumption?

Why does world wine production always exceed consumption?

In response to this ongoing problem with the once-vibrant global wine industry, there have been many comments and suggestions. For example, Rob McMillan (in the Silicon Valley Bank State of the Wine Industry Report) focuses on two solutions:

Industry members either have to “work together to create a resonant message that positively influences consumption”, or “use whatever means we have to increase efficiency in production, grape growing, and marketing”.However, neither of these is actually a solution, as neither deals with the fact that production > consumption. As Albert Einstein famously noted: “We can't solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” Using the same thinking, we would respond to over-supply by product discounting and price reductions, and by converting vineyards to other crops. This is short-term thinking, often following the current fashion (eg. Pink won’t save California wine). At worst, it is simply competing against each other, as “we all fish for the same consumers in the same pond” (7 ways to steal market share without lowering your price).

On the other hand, it seems to me that the fundamental problem is the wine industry itself, not the members of that industry. So, the members cannot resolve the problem, without a fundamental re-thinking of what that industry actually is. The industry has a customer problem — the current industry attitude seems to be: “we make this, and you should buy it”, whereas it needs to be: “you want this, and so we had better provide it”. That is, we must, as they say, change or die.

By this, I mean that so much of the current wine industry, as part of our culture, is exclusionary, rather than embracing. For example:

- wine vocabulary is often exclusionary — its taxonomies and labeling confuse people, in its perceived need to “wax poetic” when describing wine sensations (discussed in Different wine talk)

- the concept of wine tasting is exclusionary, because people need to be educated in order to appreciate wine, as well as needing to know about grape varieties and wine regions, for example (see Need to know)

- we also have follow-on exclusionary practices, such as the Certified Wine Educator credential (see The insider’s guide to the CWE exam)

- the price of good wine is often exclusionary, although there is definitely plenty of cheap stuff available (if you like that sort of thing)

- also wine tourism is often financially exclusionary — eg. we charge large

amounts for winery tastings (they were free in my day, which was the

1970s and 1980s) (see Sharing the dream: Let’s have a day of low-priced tastings)

- even the labels are exclusionary, because most jurisdictions do not require an ingredients list on labels, unlike almost all other foods (although this is slowly changing).

As recently noted (Wine industry grapples with being something only Boomers like, as younger consumers have ‘mindshare of wine half that of their elders’):

The bigger problem is the wine-drinking consumer. Some 58% of consumers over the age of 65 — essentially, the Baby Boomer generation — prefer wine to other alcoholic beverages. All other demographics are nearly 30 points lower. Even worse for vineyards is that younger consumers aren’t as interested in wine. We must show the will to change and the creativity to evolve and adopt a new approach that retains current customers while appealing to a more diverse population.

In this regard, the single most sensible article about the wine industry that I have read in years appeared recently, from Jessica Broadbent:

I will go so far as to say that “could be” in that title can be changed to “is” — it just seems to be that obvious, to me. I was going to quote parts of the article, but I then realized that I would end up quoting almost all of it; so do yourself a favor and read it all for yourself.

The bottom line with the concept of branding is that a particular product is tailored for, and marketed to, a particular group of people. Provided that the product is manufactured in an acceptable manner (sustainable, biodynamic, etc), then all of the esoteric details referred to above are optional — the customer does not necessarily know them, and does not need to, unless they choose to. Put simply, no-one is excluded in any way, but they are embraced instead. If there are enough customers for the product, then it is sustainable, long-term.

Moreover, as also noted by Rodolphe Lameyse: “Some [vineyards] will no longer make wine but will produce grapes to the specifications set by others who will supply markets under perhaps generic brands.” In other words, the grapes may not only come from one huge generic region (like most bag-in-box wines do), they could come from multiple regions, and perhaps even different regions in different years. It is the brand that is important, not the region or the grape.

So, what grape varieties are involved, and where they come from, is pretty much irrelevant, in the big scheme of things. They could even change from year to year, and still be branded the same way. This idea is horrific to much of the current wine industry, especially in Europe, and also much of the USA; but the way things are going many of them won’t be there much longer, to feel that way. This saddens me, for sure, but a failure to change would sadden me even more. Stop looking in the mirror, and start looking at your (potential) customers, instead.

Einstein on the beach, by Oslo Davis.

A central cause of declining wine consumption, in my opinion, is that wines aren't made the same way they once were. Due to current fashion, Parker score chasing, climate change, and post-phylloxera replanting, wines have become more concentrated, sweeter, more alcoholic and heavier than they were at the outset of the modern wine boom.

ReplyDeleteBaby boomers, eager to learn about wine mainly from wine critics culturally new to wine themselves, consumed wine much differently than traditional wine drinkers of past generations (guided by European tradition), more substitute cocktail than a food extension at the table. The bigger the wines, the more impressive; it matters at the table, but may be an advantage for a stand-alone beverage.

But drinking wine in larger volumes, which are less bothersome at 11-12% ABV, become troublesome at 14-16%. More headaches, more hangovers. Food moderates these ill effects, but only so much. As a result, consumers experience wine overload.

Zinfandel, once a hugely popular wine category, has alienated many regular wine drinkers because of its aggressive nature and excessive alcohol, much the same way big Australian wines have done. Pinot Noir, once the queen of wines praised for its delicacy and finesse, is more often made like Syrah or high-alcohol Grenache. Chateauneuf-du-Pape, once a staple of high-end restaurant wine lists, is today too alcoholic and assertive to provide meaningful accompaniment at the table. Even German Riesling has lost its shimmering beauty, becoming clunkier in the 21st century, I suspect due to climate warming.

All of the paradigms for "fine wine" have been distorted so much that everything we once believed about wines, longevity, lore, etc., have nearly vanished. So, in addition to the way people have overdosed on heavy wines, fine wines have also lost much of their cachet. Wines made in the 1990s and beyond don't develop in the cellar the way they did in previous generations when they became legends. There is more disappointment than ever when opening up saved bottles—they almost never live up to expectations.

There is also another interesting cultural reality that has to be factored in. Young people always look for things they can call their own—music, art and even food and wine. If your daddy doesn't understand it, you can feel superior to him and his peers. That would explain why baby boomers were drawn to wine when their Mad Men era parents were drinking cocktails. Gen Xers turned back to mixology their baby boom parents didn't understand, resurrecting classic cocktail recipes used by their great-granddaddies.

Also, don't underestimate class resentment when a generation can't afford to drink the same venerated beverages their parents (and hedge fund managers) do. Wine has always been an aspirational (rather than indigenous) beverage to much of the U.S. market, and cachet is lost if one rejects it because of its high cost. That helps explain why so many young Somms don't have Cabernet Sauvignons on their wine lists, despite the varietal's continuing dominance in overall sales. (Another factor is what Robert Parker admitted in his wine guides—Cabernet and Chardonnay are limiting food wines, and savvy wine and food people know it.)

The factors in your article explaining why wine consumption is down are all valid. Add most domestic and increasingly imported wines are just too heavy to be enjoyed regularly, and you have the answers to why wine sales have been slipping.

--Randy Kemner, Owner, The Wine Country, Signal Hill, CA

<thewinecountry@msn.

I agree with all of your points. The wine industry is, after all, a complex place, and adapting it to the modern world will not be easy, for any country, let alone for all of them together. We will have to wait and see what happens. However, at the moment I see a rash of "cautious optimism" comments appearing, which suggests that there is not much impetus for voluntary change.

DeleteMy point is that there is a difference between cheap wine and inexpensive wine. It is the recognition of this difference that would be the best introduction of young people to the joys of wine. They can have good stuff without it being expensive. Expensive is exclusionary, no matter how good it is, but inexpensive is embracing, when it is also good.

ReplyDeleteGreat Point, a preliminary step to one of the possible solution

DeleteThe widening generational divide is unmistakable, and it’s only going to deepen if the wine industry doesn’t adapt to where consumers actually are.

ReplyDeleteThe legacy of wine—as an industry, a category, and a cultural icon—is fraught with both charm and challenges. It's a rich history yet burdened by outdated practices. To some, wine is an enigma, cloaked in the allure of nature and the cosmos; to others, it’s seen as an elaborate scheme, reminiscent of the infamous "Sell me this pen" scene from The Wolf of Wall Street. It’s high time we acknowledge that wine has been co-opted by financial institutions and sales gurus, thriving on a foundation of hype and the illusion of prosperity.

The younger audience’s ability to see through these facades signals a critical juncture for the wine industry. It's time to reflect on fundamental questions: What essence does wine embody—is it a fruit derivative product or an alcoholic drink category? What values should the wine industry uphold? Is it feasible—or even desirable—for wine to distinguish itself from other alcoholic beverages? The push for unequivocal transparency in labeling is a testament to the need for change.

The dichotomy between vineyards and brands you've outlined suggests a path forward, where innovation in product formats by both grape growers and consumer packaged goods (CPG) brands could rejuvenate the industry. Exploring wine concentrates and alternative fermentation processes might pave the way for novel offerings.

However, the wine culture’s current trajectory embracing insularity, wastefulness, and corruption is alarming. The survival of the glossy print wine magazines amidst this backdrop is perplexing, highlighting an industry at odds with the values of 21-42yo who remain disinterested in joining this exclusive club. For wine to regain its appeal, it must become accessible and relevant to those who are currently outside its traditional circle.

I think that you are spot-om with your diagnosis. While I am not sure about how much young people see through the "facades", as opposed to simply preferring a wider range of beverage choices, I see that many of those choices are closer to their own hearts. Also, the wine magazines certainly seem like an anachronism, but no more so than some of the revered wine commentators, who are as old as me. Where are the young wine gurus? Their lack tells us quite a lot about the industry.

DeleteOne of the biggest impediments to reversing the current trends is the doubly myopic nature of the industry: a bubble within a bubble).

ReplyDelete1) wine is special, unique, different to all other beverages/products

2) My market (wherever I happen to be) is the only one I know/care about/understand and everything I say will be based on what I see around me

This leads Americans to lay all the blame on high octane Zinfandel and/or the 3 tier system, the French to point at local anti-alcohol legislation, the Brits to complain about excise duty and the Nordics to talk about monopolies. I could go on.

The problem, as you say, David, is global and long-standing. I think Lameyse (one of the more thoughtful members of the French industry) is right. The offer is going to have to change, in a wide range of ways