Well, we are being given opinions. Many of these opinions are actually based on real data, in the sense that there is evidence for each opinion; but others are just wishful thinking, presumably based on some bias in the opinion-giver. In the latter group are those who say: “I like wine, therefore it is good for me, in that sense.” This particular opinion is hard to argue against!

However, what I am going to write about here is the other part, where people point at some evidence in favor of their opinion. That is, they invoke medical science in support of what they are claiming. I am in favor of them doing this, for the simple reason that my professional expertise over the past 40 years has been biological science (and human beings, in spite of their claim to have a soul, quite definitely live in biological bodies).

Indeed, I used to teach university courses in biomedical experimentation — the theoretical and practical aspects of doing experiments on people.* This is important here, because experiments are where the evidence usually comes from. Opinions are fine on their own, but it is the experiment that tries to provide convincing support for the opinions. Below, I discuss some of the things that I used to teach my students — and you will see why the title of this blog post is emphatically true.

There are two issues to get clear right at the start. Evidence comes from an experiment of some sort, conducted by someone calling themselves a scientist (in this case, a biomedical scientist). We need the professional scientist because doing good experiments takes expertise. The first issue is that the experiment might not actually provide convincing evidence, in spite of good intentions The second is that it might never be possible to conduct such an experiment, in practice. Both issues apply here.

Thus, there are two basic reasons for reaching the conclusion in the title:

- a living organism is a complex thing, and what is good for one bit of the body may not be good for any other bit;

- no-one is ever going to be able to do a proper experiment to find out which bits are which, for human beings.

Complexity

It may seem trite to say that living organisms are complex, but it is worth emphasizing here, anyway. As the physicist Craig Bohren once noted:

The success of physics has been obtained by applying extremely complicated methods to extremely simple systems ... The electrons in copper may describe complicated trajectories but this complexity pales in comparison with that of an earthworm.So, this is the rub — biological scientists have taken on an enormous task, because they are studying what makes some things alive and others not. Living organisms are only alive when their whole bodies function as integrated entities. If even one tiny little bit fails, the organism may die (and biology then becomes physics!). Over the past few million years, we have learned an awful lot about how to keep particular organisms alive. We started off as hunters & gatherers, simply using whatever was alive around us. Then we developed agriculture to produce our food, and medicine to prolong our lives, thus manipulating all facets of the difference between life and death.

I don’t need to bore you with this long and involved process, but the main thing we learned is just how complex it is being alive; and, remember, we ourselves are among the most physically complicated of living beings. What is good for our hearts may be bad for our livers; and what is good for our livers may be bad for our kidneys. What is good for our minds may be bad for our hearts; and so on. We have all seen this, from the moment we were born. So, there is no practical possibility of alcohol being "good for us" in any general way — we need to specify which way we are talking about, first. This is what all biomedical scientists do, before they start their experiments — they decide which (few) bits of the complexity they will study this time.

So, any summary of the potential health benefits of wine needs to occur within this context. We cannot take any one organ on its own, and discuss the affects of alcohol on it alone, in isolation from the rest of the body. Yet, this is exactly what has been happening for the study of alcohol, to date — by necessity. Think carefully about any of the media reports you have read, and ask yourself: “Which organ are they discussing, on its own?”

William “Rusty” Gaffney has recently provided an excellent summary of the current state of knowledge (Debating the health benefits of wine: an update). He has the graphs and diagrams to make it all seem as simple as he can. But that is the problem — it ain’t simple, and never will be. I see this as a big part of the beauty of biology; but you may simply find it annoying, in your everyday.

Anyway, don’t expect a definitive answer about health benefits any time soon. There are 7.5 thousand million of us, and we are all different in one way or another (even identical twins). The effect of wine on each of us will differ in some way, however small. More importantly, even within our own bodies the affect will differ between organs. To stay alive (and enjoy life) requires us to balance the different effects; and we don’t yet know enough to do that balancing act, even approximately.

Experiments

However, let’s assume for a moment that the complexity cannot defeat us, and we are determined to find out (as all biologists are). Could we ever do a convincing experiment? That is, one that provides a pretty definitive answer to our questions about health. The answer is “no”, although that does not stop us from learning a helluva lot, anyway.

Let’s look at the practical reason for experimental failure. I used to emphasize two types of experiments to my students, only one of which provides definitive evidence. The other type of experiment provides a lot of knowledge, but in this case doubt cannot be eliminated.

The ideal experiment is what I called “manipulative”. We take a group of organisms and split it into subgroups. Each subgroup is subjected to a different experimental treatment, of some sort; and we follow the subsequent outcome, for as along as necessary. So, we deliberately manipulate the circumstances of the experiment, to investigate precisely the things we want to study, while leaving everything else the same.

This is what has been done for the current crop of vaccines, for example. A group of people volunteered to take part — you might think they are crazy, but someone has to do it, for the benefit of the rest of us. One sub-group of people were given the new vaccine, and the other sub-group were given a placebo injection (usually a salt solution) — the people are not allowed to know which experimental sub-group they are in. Both groups were then given a bit of the SARS-CoV-2 virus genome, to see whether they developed the Covid-19 disease. Normally, such an experiment (called a Phase III Trial) would be followed for 2 years; but obviously we could not wait that long in the current pandemic, before deciding that the vaccinated sub-group did better than the unvaccinated one.

The alternative type of experiment is what I called “descriptive” (or perhaps “observational”). Here, we simply follow a group of organisms through time, and use the fact that they are all different from each other to explore how they react to subsequent circumstances.

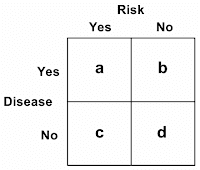

For example, in what is called a Case-Control experiment, we follow two groups of people, one of whom has a disease and one of whom hasn’t got it — any difference in the subsequent outcomes for the two groups provides us with information about having the disease. In practice, this is often the best sort of experiment that we can do on humans, because people who are prepared to take part in manipulative experiments are a bit thin on the ground.

Another example is what is called a Cohort experiment, in which we follow a single (usually large) group of people through time, to see what happens. Some of them will eventually develop a certain disease, for example, and some will not; and we can look at what sorts of people they are — what characteristics seem to pre-dispose those people to develop that particular disease. This is what has been done for the study of the benefits of the so-called Mediterranean diet, for instance. However, as we say: correlation ≠ causation, and so we do not have definitive evidence of anything actually causing anything else. However, this is far and away the most common sort of experiment that we can ethically do with human beings.

Needless, to say, almost all of the experimentation done on people, as regards the affect of alcohol, have been Cohort experiments. We follow people through time — some of them drink a lot of alcohol, some of them drink less, and some of them don't drink it at all. We then see how they turn out later in life, medically speaking. If some of them develop particular problems (heart disease, kidney failure, high blood pressure, diabetes, etc), then we can compare this to their lifestyle during the study period. We can also see which ones live longer than average (which is a better outcome).

We learn a lot from doing these descriptive experiments, but we will never get a definitive answer to whether there are health benefits to imbibing wine, or what exactly these benefits might be.

Note, as a final point, that I have not gone into the issue of where we might get these groups of people that we study, in any type of experiment. We need to address all sorts of potential sample biases, including gender, age, genetic background, cultural and socioeconomic history, etc. This is quite a topic on its own.

Conclusion

We may well be interested in knowing whether wine consumption is good or bad for us, in some amount. However, we will never actually know. The study system is very complex, and hard to study. Therefore, as Rusty Gaffney notes in his blog post: “There have been no well-executed, randomized, double-blinded, intervention trials controlled for all confounding variables.” That is, there are no manipulative experiments on complex systems.

Nevertheless, we can continue to gather evidence, and we should definitely do so. The more we know, the better will be our decisions about what to do in life. However, we will never have definitive knowledge about alcohol, and its affects on human bodies. For humans, there is always “too little” and always “too much” of everything, even for essential things like air, water and food, let alone optionals like wine. We need to live in between the upper and lower limits, and each of us has to make our own decisions about where the optimal middle might be located.

* There was an introductory course for the undergraduates in biological and biomedical sciences, and an advanced course for the postgraduate (research) students. I mention this as my attempt to provide evidence for the worth of my opinions!

David touches on the ethics of subjecting humans to experimental medical trials.

ReplyDeleteLet me volunteer these articles from The Wall Street Journal that discuss volunteer "human challenge" trials.

(I leave it to David's clever and resourceful readers to find a way to read these articles protected behind the newspaper's "paywall." Of course, for as little as U.S. $4.00 per month, one can take out an online-only access subscription.)

"One Idea for Speeding a Coronavirus Vaccine: Deliberately Infecting People" | WSJ (May 11, 2020)

Subheadline: Debate is rising among scientists about whether a so-called human challenge trial is worth the risk

"Volunteers to Be Infected With Coronavirus in Vaccine-Effectiveness Trials in U.K." | WSJ (Oct 20, 2020)

Subheadline: Controversial ‘human challenge’ trial would require injecting healthy humans with virus to gauge effectiveness of vaccines

"UK Approves Trials That Will Deliberately Infect Volunteers" | WSJ (Feb 17, 2021)

Subheadline: Controversial studies are aimed at understanding the virus and speeding vaccine development

"Covid-19 'Challenge Trial' Will Purposely Reinfect Adults" | WSJ (April 18, 2021)

Subheadline: Dozens of quarantined volunteers in U.K. to receive coronavirus in study focused on reinfection

"Researchers Ready Lab-Grown Covid-19 Delta Variant for Human Trials" | WSJ (Aug 27, 2021)

Subheadline: U.K. company is growing the highly contagious variant under tight lab controls for use in challenge studies

"The Man Who Chose to Get Covid" | Wall Street Journal Podcast (Sept 3, 2021)

"Researchers Infect Volunteers With Coronavirus, Hoping to Conquer Covid-19" | WSJ (Sept 4, 2021)

Subheadline: So-called challenge trials have long been used to study infections, but so far only the U.K. is doing them for Covid-19

"Decadeslong UK Studies Inspire New Covid-19 Trials" | WSJ (Sept 4, 2021)

Subheadline: [text cannot be copied-and-pasted into this e-mail]

Not to mention confounding effects of pretty much everything else we do or put in our bodies. I agree it would be nice to know definitively, but since that's not possible I wonder if we can't just decide to enjoy it for the things it brings us without having a definite answer.

ReplyDeleteYou and I can do so, as I alluded above. However, the medical people clearly feel the need t offer advice about what "moderate" might mean, for alcohol; and the media like to write about it.

DeleteDavid, while the specific mechanism/s are still being debated, the actual health benefit of drinking wine in terms of reduced disease and mortality is very well documented and really not up for debate. The benefits are substantial. Studies purporting to show no effect have been designed to avoid finding the usual effect, or the data interpretation has deliberately avoided mentioning the benefits.

ReplyDeleteThe potential benefits of wine are well documented, as are the potential harms. These benefits and harms depend on many factors, such as age, current health condition, and pattern of drinking. So, the issue is definitely up for debate, because of the complexity. It will continue to be debated because we can't do experiments to resolve the debate.

Delete