I do not need to tell most of you about the current problems being faced by the wine industry, and the future sales of wine, particularly in the USA. Back in 1924 the issues facing the newly formed International Wine Office were said to be fraud and Prohibition (

The OIV “at a crossroads” in its history). Now 100 years later, with the organization now renamed the International Organisation of Vine & Wine, Prohibition may be returning in the USA, and wine sales are declining worldwide (

Is wine facing Prohibition 2.0?).

There are an awful lot of people reacting to this situation, with many of them saying very interesting and valuable things. I will be linking some of these below; but at the same time I am hoping that I can say something of value myself. You see, my professional expertise is in scientific experiments, as I am a (recently retired) university biological scientist. And I mean what I have said in the title above, professionally.

Scientists conduct experiments, which are intended to provide the

evidence upon which societal decisions are made. (I used to teach a course on

Introduction to Experimental Design, for university biology students.) We use these experiments to study

cause-and-effect in a rigorous manner (e.g. the effect of alcohol on

people). Most importantly, we know the benefits and limits of experiments; and when

it comes to studying the effects of alcohol on people, the latter

out-weigh the former. This is what I will be writing about here.

Tom Wark has recently listed 10 of the important recent articles speaking against alcohol, covering all parts of the media:

Can the wine industry muster the will to push back on propaganda? I will not be pushing back, but I will instead be pointing out that there shouldn’t

be anything to be pushing back against.

I have pointed out in a recent post:

Why alcohol experiments are problematic. I will discuss part of this below. Furthermore, I have also asked:

Has the WHO lost its way regarding alcohol? Yes, I answered. In particular, I also asked:

Has WHO got it wrong with its new zero-alcohol policy? Probably, I said. So, I have not been silent on the issue; and I will continue here.

Let me start by also saying that I do not

know what level of alcohol consumption starts to cause medical problems, or whether there

is some level below which alcohol actually has benefits (the so-called French Paradox). The purpose of this blog post is to point out that

no-one knows, experimentally. This is because it would be impossible / illegal / unethical to do such an experiment, at least in a free society. So, we will probably never know.

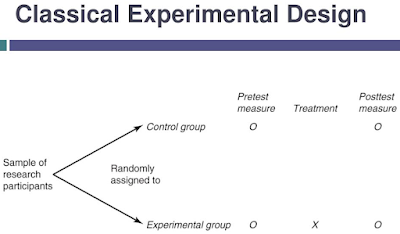

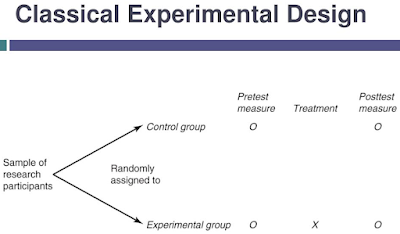

The basic issue is relatively straightforward. The next picture shows you how to do a simple scientific experiment — a single group of people is randomly split into two, one of which gets the “Treatment” (in our case they drink alcohol) and the other is the “Control” (they do not drink any alcohol). If we have done this manipulation properly, then any difference we observe afterwards between the two groups of people must be due to the treatment (Alcohol).

There are also a host of technical requirements, of course, for such a “Manipulative” study. For example, the Control group of people should drink a substitute for alcohol, called a “Placebo”, to make the actions of the two groups of people as similar as possible. Also, the experimenters themselves should be “Blinded”, so that those looking after the experimental people do not know whether any given person is in the Treatment or Control group. We could also have several different groups of Treatment people, of course, with each group drinking a different amount of alcohol. These are all important points, and there are others.

As I noted above, you cannot do this sort of manipulation on real human beings. All you can realistically do is what we call an “Observational” (or “Descriptive”) study, in which we observe a large (see my post:

Why do people get hung up about sample size?) group of people, who drink a whole range of different amounts of alcohol. We then try to relate their differences in behaviour to the amount of alcohol they have consumed. We call this an Observational study because all we do is observe the people, rather than manipulate them. I have compared the two types of studies in the next table below (and you can also read about them elsewhere online; e.g.

Experiment vs Observational study: similarities & differences).

These Observation studies are not as good as a proper Treatment/Control experiment, but when it is all you have, then needs must. Observational studies cannot reveal cause-and-effect in a rigorous manner, but can merely give us hints. In particular, as I noted in a previous post, we need to be careful about:

Misinterpreting statistical averages — we all do it.

As far as the effects of alcohol are concerned, there is at least one well-balanced summary of the current situation regarding the sorts of experiments we have been able to do, by Louis Maximilian Buja (2022):

The history, science, and art of wine and the case for health benefits: perspectives of an oenophilic cardiovascular pathologist. *

One of the important points that this author makes is that risk from alcohol does not start at

any particular exposure. It is how much alcohol a person chooses to consume continuously that can cause a problem. This makes the World Health Organization current position so problematic:

WHO demonizing of alcohol, are their alarms real? The WHO does a disservice to the problem by staking out a radical position.

In addition, we do need to concern ourselves about:

How quickly does the alcohol disappear from the body and can you sober up faster? Notably, there are individual differences between people, so any one generalization is hard to make.

This brings us to

Dr. Tim Stockwell, a professor in the Department of Psychology at the University of Victoria. He has been

described as “the man who is almost single-handedly responsible for convincing the public there is no safe level of drinking.” He has been at it for a couple of decades (e.g.

A global phenomenon), and he has made a lot of noise recently; for example:

Professor Tim Stockwell versus the J-curve. A good introduction and evaluation is:

Moderate drinking and its enemies.

Well, being a university professor does not make you an expert outside the field of your own expertise. Being concerned, as a social psychologist might, about the cultural and personal effects of alcoholism is very laudable; but determining whether alcohol is the cause

or the symptom of any perceived social problem is another thing altogether. [His

Severity of Alcohol Dependence Questionnaire, for example, is descriptive rather than experimental.]

In particular, given his background, Stockwell’s writing about the elucidation of cause and effect is not written from the perspective of experiments, rather than being written by an observer. Now, this may provide a broader perspective — an outsider can sometimes contribute to conceptual clarity. However, experimenters have an understanding of experiments, how to conduct them, and how to interpret them — these are things that non-experimentalist writers about experiments surprisingly often fail to comprehend.

The main point that I wish to make here is that

none of the research publications that Stockwell cites in support of his radical position on alcohol are of the Treatment/Control type, for the reason explained above. They are

all of the Observational type, as described above. So, the evidence for his claims is much more limited than he seems to give credit for, as he has no cause-and-effect data.

One publication that I found particularly distressing, as a scientist, was this one:

How several hundred lancet co-authors lost a million global alcohol-caused deaths. In it, Tim Stockwell tries to convince us that there has been scientific hanky-panky, in which the data from a first study was manipulated unfairly in a second study. However, what Stockwell does instead is demonstrate his own lack of understanding of science.

You see, the authors of the second study sub-divided the dataset from the first study into coherent sub-groups, and looked at each sub-group separately. This is the sort of thing that you

have to do in Observational studies, to deal with the limitations that I discussed above — it is not a Treatment/Control experiment, and so we have to be very careful about interpreting our data. So, the data interpretation in the second study was likely to be much more justified than the data interpretation in the first study, which lumped all of the people into one group.

If you want to read more about these sorts of issues, then these two professional publications are a good place to start:

ConclusionThe bottom line is simple: there never has been, and probably never will be, a proper Manipulative scientific experiment studying the effect of alcohol on humans. It would be unethical and probably illegal to ever conduct such an experiment. All we will ever have is Descriptive studies; and these are hard to set up validly, and they require very careful interpretation.

So, any pronouncement that

all effects of alcohol are bad is pure poppy-cock. There are observed benefits and drawbacks, depending on the amount consumed and the circumstances under which it is consumed. That is likely to be as far as we can ever go, as scientists. As Tom Wark recently noted:

On alcohol and cancer — be happy, you're gonna be just fine; or as

Paracelsus (1493–1541) famously stated: “Whether wine is a nourishment, medicine or poison is a matter of dosage.”

* Here is the author’s

Conclusion:

Epidemiological and biological evidence continues to accumulate showing that alcoholic beverages in moderation have a positive effect on cardiovascular health. Some studies give the edge to wine, especially red wine, whereas other studies show favorable benefits for beer and spirits. Despite a lack of consensus on a specific type of beverage, mounting evidence suggests that ethanol and polyphenols within wine can synergistically confer benefits against chronic cardiovascular diseases, mostly ischemic heart disease (IHD). This is particularly true for red wine when consumed as a component of the Mediterranean diet and lifestyle.