Things like global climate change (the negative effects of which substantially outweigh the positives), biodynamic agriculture, regenerative viticulture, sustainable winemaking, and worldwide over-supply are all undoubtedly big issues in the wine industry, and they rightly occupy a large amount of space in the wine-industry media. However, there is one issue that far exceeds all others — not many people want to drink wine any more. These other issues cannot be addressed properly until the latter one is addressed first; and so I will discuss it here.

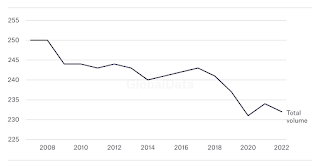

The above graph shows recent world wine consumption (mhl) since 2007, as released by the International Organisation of Vine and Wine (OIV). It is not a pretty sight.

There seem to be two issues that combine to create this disaster:

- declining consumption of alcohol among younger drinkers

- declining consumption of wine relative to other forms of alcohol, especially cheaper wines.

One of the basic consequences of this issue is, of course, that global wine production always exceeds consumption, as I have written about before:

When will world wine consumption finally catch up with production?

Why does world wine production always exceed consumption?

Why does world wine production always exceed consumption?

In response to this ongoing problem with the once-vibrant global wine industry, there have been many comments and suggestions. For example, Rob McMillan (in the Silicon Valley Bank State of the Wine Industry Report) focuses on two solutions:

Industry members either have to “work together to create a resonant message that positively influences consumption”, or “use whatever means we have to increase efficiency in production, grape growing, and marketing”.However, neither of these is actually a solution, as neither deals with the fact that production > consumption. As Albert Einstein famously noted: “We can't solve problems by using the same kind of thinking we used when we created them.” Using the same thinking, we would respond to over-supply by product discounting and price reductions, and by converting vineyards to other crops. This is short-term thinking, often following the current fashion (eg. Pink won’t save California wine). At worst, it is simply competing against each other, as “we all fish for the same consumers in the same pond” (7 ways to steal market share without lowering your price).

On the other hand, it seems to me that the fundamental problem is the wine industry itself, not the members of that industry. So, the members cannot resolve the problem, without a fundamental re-thinking of what that industry actually is. The industry has a customer problem — the current industry attitude seems to be: “we make this, and you should buy it”, whereas it needs to be: “you want this, and so we had better provide it”. That is, we must, as they say, change or die.

By this, I mean that so much of the current wine industry, as part of our culture, is exclusionary, rather than embracing. For example:

- wine vocabulary is often exclusionary — its taxonomies and labeling confuse people, in its perceived need to “wax poetic” when describing wine sensations (discussed in Different wine talk)

- the concept of wine tasting is exclusionary, because people need to be educated in order to appreciate wine, as well as needing to know about grape varieties and wine regions, for example (see Need to know)

- we also have follow-on exclusionary practices, such as the Certified Wine Educator credential (see The insider’s guide to the CWE exam)

- the price of good wine is often exclusionary, although there is definitely plenty of cheap stuff available (if you like that sort of thing)

- also wine tourism is often financially exclusionary — eg. we charge large

amounts for winery tastings (they were free in my day, which was the

1970s and 1980s) (see Sharing the dream: Let’s have a day of low-priced tastings)

- even the labels are exclusionary, because most jurisdictions do not require an ingredients list on labels, unlike almost all other foods (although this is slowly changing).

As recently noted (Wine industry grapples with being something only Boomers like, as younger consumers have ‘mindshare of wine half that of their elders’):

The bigger problem is the wine-drinking consumer. Some 58% of consumers over the age of 65 — essentially, the Baby Boomer generation — prefer wine to other alcoholic beverages. All other demographics are nearly 30 points lower. Even worse for vineyards is that younger consumers aren’t as interested in wine. We must show the will to change and the creativity to evolve and adopt a new approach that retains current customers while appealing to a more diverse population.

In this regard, the single most sensible article about the wine industry that I have read in years appeared recently, from Jessica Broadbent:

I will go so far as to say that “could be” in that title can be changed to “is” — it just seems to be that obvious, to me. I was going to quote parts of the article, but I then realized that I would end up quoting almost all of it; so do yourself a favor and read it all for yourself.

The bottom line with the concept of branding is that a particular product is tailored for, and marketed to, a particular group of people. Provided that the product is manufactured in an acceptable manner (sustainable, biodynamic, etc), then all of the esoteric details referred to above are optional — the customer does not necessarily know them, and does not need to, unless they choose to. Put simply, no-one is excluded in any way, but they are embraced instead. If there are enough customers for the product, then it is sustainable, long-term.

Moreover, as also noted by Rodolphe Lameyse: “Some [vineyards] will no longer make wine but will produce grapes to the specifications set by others who will supply markets under perhaps generic brands.” In other words, the grapes may not only come from one huge generic region (like most bag-in-box wines do), they could come from multiple regions, and perhaps even different regions in different years. It is the brand that is important, not the region or the grape.

So, what grape varieties are involved, and where they come from, is pretty much irrelevant, in the big scheme of things. They could even change from year to year, and still be branded the same way. This idea is horrific to much of the current wine industry, especially in Europe, and also much of the USA; but the way things are going many of them won’t be there much longer, to feel that way. This saddens me, for sure, but a failure to change would sadden me even more. Stop looking in the mirror, and start looking at your (potential) customers, instead.

Einstein on the beach, by Oslo Davis.