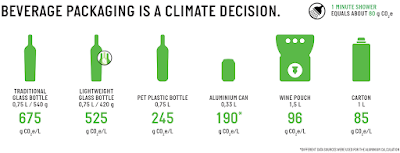

The obvious follow-up question is then: what are the package options, and how do they stack up against each other? This is what I will cover here, by looking at each type.

It is important to start by noting that it is both the manufacture and the transport of the bottles that create the issue — glass bottles involve a lot of heat to be made, and they are heavy to transport; and both of these produce a lot of carbon emissions. This is why we need to consider alternatives to using new (standard) bottles for every wine vintage. Mind you, the current shortages of glass bottles may force us anyway (Spiralling costs are blowing wine buying rules ‘out of the water’).

Refilling your own bottles

To me, it is obvious that we should start with this option, as re-use is always superior to recycling. We also get control of a lot of the transport, since we do it ourselves, and we decide what we are going to store our wine in (and thus drink it from). The idea is for us to go ourselves to the retailer (or producer), and have them fill up the containers we bring with us. Obviously, if these are glass bottles then they should be ones that we have used before, and then thoroughly cleaned, rather than us bringing new ones each time.

There is nothing intrinsically new about this idea, since some parts of the world already do this for supermarket hygiene products like soap and shampoo. There are already a number of such systems currently being used for alcohol, although they seem to exist only in retailers principally designed for this purpose. One obvious issue for retailers is the floor space required for a refill station; and deciding on a suitable bottle closure is not straightforward either (And now for something completely different).

Nevertheless, a couple of examples of refill bottling schemes for spirits were discussed at the recent Vinexposium (What’s the future of alternative wine packaging?). At the moment, one scheme has "around 20% of people return the bottle to be refilled", although 80% is the target. As an example for a winery, LJ Crafted Wines has patented a device that’s inserted into the barrel, from which they sell all their wines directly. It takes 3-4 months to sell the wine, so it needs to be kept fresh in the opened barrel for that length of time. * There is also an Australian company called ReWine, which uses its own versions of Flextanks to transport wine in large quantities directly from a winery to its warehouse facilities, to then subdivide into a unique barrel system for customers to have their bottles filled and refilled, dispensed under nitrogen with 30% CO2 (And now for something completely different). It also uses a Nova Twist closure, because you can’t re-use a screw-cap.

Return bottles to be re-used

The obvious next alternative is to have the producers and retailers re-fill the used bottles. That is, the bottles are returned to the retailer, and the producer cleans and re-uses them. Otherwise, it is basically the same as the previous section. This seems a bit more likely in practice, than having us re-fill them ourselves, as we simply return them the next time we visit the retailer. Indeed, a recent Rabobank report suggests that returnable, refillable bottles are not only the most sustainable packaging solution, they could also become the most economical.

At the moment, here is Sweden we have returnable glass bottles for many brands of beer (The change at Systembolaget that many missed). The bottles are marked as returnable, and we pay a small refundable deposit on them. Sadly, of the 32.6 million liters sold in 2021, an estimated 86% of the bottles were not returned. This system obviously needs improvement, before being applied to wine bottles.

There is nothing unusual about such a system, of course, in many places around the world. However, in places like California, many aluminum, plastic and glass containers have a refundable recycling fee, but many don’t — whether the bottle fee applies depends as much on what the bottle holds as what it’s made of. Nevertheless, the California bottle fee is to apply to wine and spirits in 2024; and a similar Proposed container deposit scheme expansion rattles NSW wine industry.

PET bottles and aluminium cans

I might as well lump these two together, even though some drinkers might feel that there is a psychological difference in drinking from each of them. The idea, however, in both cases, is that these are food-grade containers (just like glass), and that they require much less energy to produce, and they can be recycled conveniently (but not re-used, as can glass). Perhaps the most practical suggestion is that these can be used for wine that will be consumed in the shorter term than we might expect for glass bottles (up to a year?); and let’s face it, that is actually most wines.

As noted above, here in Sweden we pay a deposit for all of these containers, whether from the supermarket or an alcohol retailer. That deposit is credited to us when we next visit a supermarket, as there are machines conveniently placed next to the entrances. We get a receipt, which we can cash in the supermarket, or have credited to our supermarket bill at the check-out. I noted last week that the Nordic retailers are leading the way forward (Can the Nordic monopolies turn the drinks world green?), and this is one of the ways.

The issue here, of course, will be to get wine drinkers to drink from a can (just like beer drinkers), or be persuaded that a PET bottle can contain high-quality wine. This sort of thing can be done, of course, as the wine-makers of Clare Valley (in South Australia) showed, when they unilaterally switched from corks to screw-caps for their 2000 vintage (Clare Valley celebrates 20 years of the screwcap revolution). Indeed, it has been reported that cans saw the greatest increase as a proportion of wine packaging market in the 2010s (A changing environment for wine packaging).

In this regard, Garçon Wines, based in the U.K., has been using flat bottles made from pre-existing and recycled PET plastic, with some success (And now for something completely different). A similar bottle has been developed in Australia, by Packamama (Eco-bottle targets wine industry’s carbon hotspot). Also, it has been reported that Miguel Torres Chile will switch to flat PET bottles in Sweden.

Paper bottles

I have put this in a separate grouping because of potential issues with recycling; but otherwise this is simply part of the previous group. There are different variants for "aseptic cartons", from waxed cardboard boxes, such we use for milk or cream, to more sophisticated systems. Some people are excited by examples of this option (Kate Hawkings on the future of alternative wine packaging):

it’s a bag-in-box but in the shape of a normal wine bottle. Made from 94% recycled (and recyclable) paperboard with a recyclable liner, it’s around a fifth the weight of a glass bottle, has a sixth of its carbon footprint and, crucially, is pleasingly tactile to use and to hold.The issue, for me, is the extent to which cardboard / paper and plastic packaging actually gets recycled, in practice. Worldwide, we (usually) pay no deposit fee, and so recycling is entirely optional. Here in Sweden, we have a very efficient system (we have two trash cans collected, one of them with separate sections for plastic and paper packaging). Sadly, it is often reported that the subsequent treatment of plastic packaging, for example, is not the best — indeed, it has been claimed that, even though 85% is recycled, much of this goes to China, where it is placed in landfill. Cardboard is apparently dealt with much better.

Bag in box

Most wine drinkers are familiar with this one, so I don’t need to say much. Way back in 1964, an Australian wine-maker (Thomas Angove) decided to adapt the way in which battery acid is transported, immediately recognizing its potential for wine drinking. The main subsequent trick was to put a tap on the bag (in 1967), rather than a clothes-peg. For our purposes here, it is basically a plastic bag inside a cardboard box, so its manufacture and disposal advantages are pretty much as discussed above.

One of the extra advantages of this packaging style is the size of the container. Larger containers have less packaging per unit of content, and these commonly contain 3–4 liters of wine, which exceeds that commonly used for the alternatives discussed above. So, they compare very well in terms of sustainability (Economic and environmental sustainability of wine packaging systems).

The main practical issue is that it has been adopted principally for inexpensive wines in large amounts. So, the task of getting premium wine drinkers to use it will be a major undertaking. Apparently, “only 37% of regular wine drinkers consider bag-in-box to be a sustainable form of wine packaging” (When in Rome is on a mission with alternative wine packaging).

Light-weight glass bottles

Having considered the above options, what if we decide to continue using glass bottles, at least for premium wines? After all, glass is considered to be good for long-term storage (a decade or two?), as well as for sparkling wines. Otherwise, a heavy glass bottle is simply a subjective image that some people associate with high quality contents.

Alko, the Finnish national alcohol retailer, has categorized wine bottles weighing less than 420 grams as “environmentally friendly packaging” — after all, a 330 g glass bottle will protect wine equally well as a bottle weighing several kilograms (Wine bottles: a heavy price). Recently, an industry collaboration in Australia released a lightweight Reverse Taper bottle weighing 420 grams, which is 195 g less than the standard Reverse Taper bottle, and this equates to an 18% reduction in emissions (Premium wine packaging gets a sustainable makeover).

Things are somewhat different for sparkling wines, since there is internal gas pressure. Currently, the champagne house Telmont is testing the lightest champagne bottle, but this only takes the standard 835 grams down to 800 g. So, things do not look too sustainable in the sparkling wine world.

There is at least one U.S. vineyard that long ago converted its entire line of wines to lightweight glass bottles (Fetzer Vineyards converts to lightweight glass bottles). In the process, they expected to have “an average annual decrease of 16 percent in glass usage, a reduction of some 2,100 tons, and a 14 percent drop in greenhouse gas emissions, an estimated 3,000 tons of CO2”.

Different bottle shapes, etc

So, what if we focus on transportation rather than the manufacture? In that case, it is the shape of the bottle that can be improved, as well as its weight. Here, flat plastic bottles are an example of the new wine packaging that is being launched globally; and watertight wood-fibre packaging has also been developed in Finland (New winds in wine packaging: lightweight and environmentally friendly). I am not so sure about the latter; but a container that fits in your hip pocket has long been seen as a good thing by certain alcohol consumers.

This issue combines of course, with wine tourism, as Robert Joseph has pointed out (Heavy bottles and wine tourism - and their carbon footprint). Tourism generates a lot of CO2, and so the products sold to them should be as environmentally friendly as possible. **

Furthermore, transporting bulk wine is more sustainable than bottled wine, since it does not involve the retail package at all; and it is continually increasing (Global trade of bulk wine reached historical levels in 2021). All that has to happen is for consumers to learn to associate the bulk stuff with high quality (Drinks trade must change its attitude to bulk wine) — apparently, premium bulk is gaining in share (Bulk rides high as global trade in wine grows).

Conclusion

There are thus lots of options for the wine industry to move forward, into a more sustainable future. Many of these are discussed further in the International Wineries for Climate Action (IWCA) 2nd Annual Report. However, it has been noted that corporations might well embrace sustainability (in theory) but still struggle to act (in practice). Nevertheless, the wine industry is much better placed for a sustainable future than things like cryptocurrencies, for example (New York governor signs first-of-its-kind law cracking down on Bitcoin mining)!

* Thanks to Alan Goldfarb for alerting me to this.

** According to Wine Australia, less than half of all people who visit wineries are motivated to taste and buy wines. So: Think of visitors as ‘wine tourists’ — not wine consumers.