Monday, December 27, 2021

The value of exporting wine to Russia

The Russians do make their own stuff, mostly in the North Caucasus region (the very south-west of the country). Oddly, they do also seem to want to call their sparkling wine “champagne”, even when they make it themselves, rather than the French doing it (Only wines made in Russia can be called champagne under new Putin law).

As well as drinking their own wine themselves, they do export some of it. Indeed, in 2020 this amounted to 5.1 million liters or US$9.9 million (according to the UN Comtrade: International Trade Statistics database). It went to neighboring countries like the Ukraine (2.8 million liters, or 55%), China (12.5%), Georgia (11.5%), Kazakhstan (7.5%), Belarus (6.5%), Moldova (3%), Latvia (2%), and Kyrgyzstan (1%). This is why most of you have never tasted any of it.

However, their climate is not the best for growing grapes (not yet, anyway), and so they do import quite a bit of wine. The AAWE recently listed the top 20 sources of import for 2019 (sourcing their data from Comtrade), which accounted for 93% of the total import volume (657 million liters) and 94% of the total value (US$1.15 billion). Most of the wine comes from only a few places, with the Big Four countries accounting for 68% of the volume and 74% of the value.

I have plotted the data in the graph, where the horizontal axis shows the volume (note the logarithmic scale), the vertical axis shows the price per liter, and each point represents one of the 20 import countries. The pink line represents the average total value (ie. volume x price) — those countries to the right of this line contributed more than the average value across all countries. So, the vast majority of the wine value comes from Italy (IT), France (FR), Spain (ES) and Georgia (GE).

Note that there is more than one way to skin the proverbial cat. For example, Spain (ES) provides the largest volume, but at a very low price point, whereas France (FR) provides only 40% of that volume, but at 2.5 times the price — this results in roughly the same total value of wine imported from each of the two countries.

Uzbekistan (UZ) and Moldova (MD) provide the cheapest wine, while New Zealand (NZ) and Austria (AT) provide the most expensive stuff. The USA (US) and Australia (AU) provide less wine than New Zealand but more than Austria, and at a cheaper price point. Chile (CL), Portugal (PT) and South Africa (ZA) follow most of the Big Four countries in price, but with considerably less volumes.

Russia is the 9th most populous country on the planet, with c. 40% of the population of the USA; so this is potentially a large export market for the wine industry. It may be a better bet than the other large countries (India, Indonesia, Pakistan, Nigeria, Bangladesh), which are not known as big wine consumers. * Unfortunately, Russia may not be politically or economically any more reliable than China has turned out to be, as a trading partner. Nevertheless, it may be worth a quick look by the Australians, given their loss of the China market (China slams Australian wine with 218% tariffs for 5 years).

* The USA is the third most populous country, after China and India. There has been a continuous rise in per person wine consumption in the USA from the end of Prohibition, finally resulting in the US taking the global lead in total wine consumption from the year 2010 onward (The rise of the USA as the world's biggest wine consumer ).

Monday, December 20, 2021

Why we are never going to know whether wine is good for us, or not

Well, we are being given opinions. Many of these opinions are actually based on real data, in the sense that there is evidence for each opinion; but others are just wishful thinking, presumably based on some bias in the opinion-giver. In the latter group are those who say: “I like wine, therefore it is good for me, in that sense.” This particular opinion is hard to argue against!

However, what I am going to write about here is the other part, where people point at some evidence in favor of their opinion. That is, they invoke medical science in support of what they are claiming. I am in favor of them doing this, for the simple reason that my professional expertise over the past 40 years has been biological science (and human beings, in spite of their claim to have a soul, quite definitely live in biological bodies).

Indeed, I used to teach university courses in biomedical experimentation — the theoretical and practical aspects of doing experiments on people.* This is important here, because experiments are where the evidence usually comes from. Opinions are fine on their own, but it is the experiment that tries to provide convincing support for the opinions. Below, I discuss some of the things that I used to teach my students — and you will see why the title of this blog post is emphatically true.

There are two issues to get clear right at the start. Evidence comes from an experiment of some sort, conducted by someone calling themselves a scientist (in this case, a biomedical scientist). We need the professional scientist because doing good experiments takes expertise. The first issue is that the experiment might not actually provide convincing evidence, in spite of good intentions The second is that it might never be possible to conduct such an experiment, in practice. Both issues apply here.

Thus, there are two basic reasons for reaching the conclusion in the title:

- a living organism is a complex thing, and what is good for one bit of the body may not be good for any other bit;

- no-one is ever going to be able to do a proper experiment to find out which bits are which, for human beings.

Complexity

It may seem trite to say that living organisms are complex, but it is worth emphasizing here, anyway. As the physicist Craig Bohren once noted:

The success of physics has been obtained by applying extremely complicated methods to extremely simple systems ... The electrons in copper may describe complicated trajectories but this complexity pales in comparison with that of an earthworm.So, this is the rub — biological scientists have taken on an enormous task, because they are studying what makes some things alive and others not. Living organisms are only alive when their whole bodies function as integrated entities. If even one tiny little bit fails, the organism may die (and biology then becomes physics!). Over the past few million years, we have learned an awful lot about how to keep particular organisms alive. We started off as hunters & gatherers, simply using whatever was alive around us. Then we developed agriculture to produce our food, and medicine to prolong our lives, thus manipulating all facets of the difference between life and death.

I don’t need to bore you with this long and involved process, but the main thing we learned is just how complex it is being alive; and, remember, we ourselves are among the most physically complicated of living beings. What is good for our hearts may be bad for our livers; and what is good for our livers may be bad for our kidneys. What is good for our minds may be bad for our hearts; and so on. We have all seen this, from the moment we were born. So, there is no practical possibility of alcohol being "good for us" in any general way — we need to specify which way we are talking about, first. This is what all biomedical scientists do, before they start their experiments — they decide which (few) bits of the complexity they will study this time.

So, any summary of the potential health benefits of wine needs to occur within this context. We cannot take any one organ on its own, and discuss the affects of alcohol on it alone, in isolation from the rest of the body. Yet, this is exactly what has been happening for the study of alcohol, to date — by necessity. Think carefully about any of the media reports you have read, and ask yourself: “Which organ are they discussing, on its own?”

William “Rusty” Gaffney has recently provided an excellent summary of the current state of knowledge (Debating the health benefits of wine: an update). He has the graphs and diagrams to make it all seem as simple as he can. But that is the problem — it ain’t simple, and never will be. I see this as a big part of the beauty of biology; but you may simply find it annoying, in your everyday.

Anyway, don’t expect a definitive answer about health benefits any time soon. There are 7.5 thousand million of us, and we are all different in one way or another (even identical twins). The effect of wine on each of us will differ in some way, however small. More importantly, even within our own bodies the affect will differ between organs. To stay alive (and enjoy life) requires us to balance the different effects; and we don’t yet know enough to do that balancing act, even approximately.

Experiments

However, let’s assume for a moment that the complexity cannot defeat us, and we are determined to find out (as all biologists are). Could we ever do a convincing experiment? That is, one that provides a pretty definitive answer to our questions about health. The answer is “no”, although that does not stop us from learning a helluva lot, anyway.

Let’s look at the practical reason for experimental failure. I used to emphasize two types of experiments to my students, only one of which provides definitive evidence. The other type of experiment provides a lot of knowledge, but in this case doubt cannot be eliminated.

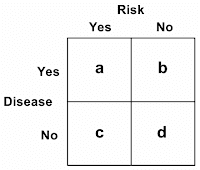

The ideal experiment is what I called “manipulative”. We take a group of organisms and split it into subgroups. Each subgroup is subjected to a different experimental treatment, of some sort; and we follow the subsequent outcome, for as along as necessary. So, we deliberately manipulate the circumstances of the experiment, to investigate precisely the things we want to study, while leaving everything else the same.

This is what has been done for the current crop of vaccines, for example. A group of people volunteered to take part — you might think they are crazy, but someone has to do it, for the benefit of the rest of us. One sub-group of people were given the new vaccine, and the other sub-group were given a placebo injection (usually a salt solution) — the people are not allowed to know which experimental sub-group they are in. Both groups were then given a bit of the SARS-CoV-2 virus genome, to see whether they developed the Covid-19 disease. Normally, such an experiment (called a Phase III Trial) would be followed for 2 years; but obviously we could not wait that long in the current pandemic, before deciding that the vaccinated sub-group did better than the unvaccinated one.

The alternative type of experiment is what I called “descriptive” (or perhaps “observational”). Here, we simply follow a group of organisms through time, and use the fact that they are all different from each other to explore how they react to subsequent circumstances.

For example, in what is called a Case-Control experiment, we follow two groups of people, one of whom has a disease and one of whom hasn’t got it — any difference in the subsequent outcomes for the two groups provides us with information about having the disease. In practice, this is often the best sort of experiment that we can do on humans, because people who are prepared to take part in manipulative experiments are a bit thin on the ground.

Another example is what is called a Cohort experiment, in which we follow a single (usually large) group of people through time, to see what happens. Some of them will eventually develop a certain disease, for example, and some will not; and we can look at what sorts of people they are — what characteristics seem to pre-dispose those people to develop that particular disease. This is what has been done for the study of the benefits of the so-called Mediterranean diet, for instance. However, as we say: correlation ≠ causation, and so we do not have definitive evidence of anything actually causing anything else. However, this is far and away the most common sort of experiment that we can ethically do with human beings.

Needless, to say, almost all of the experimentation done on people, as regards the affect of alcohol, have been Cohort experiments. We follow people through time — some of them drink a lot of alcohol, some of them drink less, and some of them don't drink it at all. We then see how they turn out later in life, medically speaking. If some of them develop particular problems (heart disease, kidney failure, high blood pressure, diabetes, etc), then we can compare this to their lifestyle during the study period. We can also see which ones live longer than average (which is a better outcome).

We learn a lot from doing these descriptive experiments, but we will never get a definitive answer to whether there are health benefits to imbibing wine, or what exactly these benefits might be.

Note, as a final point, that I have not gone into the issue of where we might get these groups of people that we study, in any type of experiment. We need to address all sorts of potential sample biases, including gender, age, genetic background, cultural and socioeconomic history, etc. This is quite a topic on its own.

Conclusion

We may well be interested in knowing whether wine consumption is good or bad for us, in some amount. However, we will never actually know. The study system is very complex, and hard to study. Therefore, as Rusty Gaffney notes in his blog post: “There have been no well-executed, randomized, double-blinded, intervention trials controlled for all confounding variables.” That is, there are no manipulative experiments on complex systems.

Nevertheless, we can continue to gather evidence, and we should definitely do so. The more we know, the better will be our decisions about what to do in life. However, we will never have definitive knowledge about alcohol, and its affects on human bodies. For humans, there is always “too little” and always “too much” of everything, even for essential things like air, water and food, let alone optionals like wine. We need to live in between the upper and lower limits, and each of us has to make our own decisions about where the optimal middle might be located.

* There was an introductory course for the undergraduates in biological and biomedical sciences, and an advanced course for the postgraduate (research) students. I mention this as my attempt to provide evidence for the worth of my opinions!

Monday, December 13, 2021

Wine scores and Top 100 lists

In normal human language, opinions are usually expressed using some sort of adjectives (good, acidic, watery, sweet, etc), but wine scores express the opinion as a number. In one sense, this can help make the opinion clear (a 95-point wine is claimed to be better, in some sense, than a 90-point wine). However, contradicting this is the tendency to treat a number as having a strict mathematical property. This makes little obvious sense, because opinions, and adjectives, are not mathematical.

In a blog post (The fundamental problem with wine scores) I noted this issue explicitly: the single wine-quality number is trying to do too many things all at once (formally: wine scores represent multidimensional properties that have been summarized as a single point in one dimension). With words, we can describe anything we want to, because we can use as many words as we need; but a wine-quality score is one number only.

This issue becomes obvious when we try to compare wine-quality scores across different wine types or terroirs, and, especially, between different tasters (see The sources of wine quality-score variation). The basic issue is that we cannot tell what any numerical similarity or difference of scores actually means (Why comparing wine-quality scores might make no sense). In particular, it is not obvious what calculating an average of quality scores might actually mean, although some well-known web sites do this regularly; and it was also done for the infamous Judgment of Paris (see: A mathematical analysis of the Judgment of Paris).

We would all, I presume, prefer it if any one commentator, or set of commentators from a single publication, is consistent. If this is so, then we could at least search for value-for-money wines by comparing scores to prices (The relationship of price to wine-quality scores). This is possibly the most valuable use of a wine score!

However, one thing that still needs addressing is the combining of wine-quality scores to produce a "best of" list. The fact that the scores are numbers does not mean that you can simply pool them from various sources. Indeed, as I have noted, the annual Wine Spectator Top-100 lists from 1988 to 2019 showed considerable variation through time.

To emphasize this point, we can look at the recent Top 100 Wines of 2021 from James Suckling and his colleagues. This is not simply a compilation of the best–scoring wines from this year, based on the 11 individual Top-100 lists from that year (Argentina, Australia, Austria, Chile, China, France, Germany, Italy, New Zealand, Spain, USA). Such a thing would not be very useful, on its own — this would be an aggregation of numbers, not a synthesis of opinions.

In this case, there are at least nine opinions to be synthesized: “Tasting team members James Suckling, Claire Nesbitt and Kevin Davy held down the fort in Hong Kong, while Jo Cooke, Stuart Pigott, Zekun Shuai, William McIlhenny, Nathan Slone and Nick Stock tasted and rated thousands of more bottles on the road in Europe and the United States as well as South Australia and China.”

James notes that: “The main criteria that went into selecting this year’s list of the best 100 wines of the world was quality ... Then we looked at pricing, and finally what we call the ‘wow’ factor. The latter are wines that excite us emotionally as well as technically as tasters.” The graph below lists all of the 100 wines in rank order, horizontally, with their assigned score shown by the vertical bar (one bar per wine).

As you can see, the Top 100 wines all scored between 98 and 100 points. However, you will note that even scoring 98 could still get a wine into the top 20 (the best of them is ranked 20th). Moreover, scoring 100 did not even guarantee that a wine got into the top 60 (the last is 63rd). Indeed, according to the website, there were 38 100-point wines (of the almost 25,000 wines tasted), but only 25 made it into the Top 100 (some of the others had only a small production, and were thus disqualified). Top scoring is apparently a tricky business for a wine (see: How many 100-point scores do critics really give?).

So, some wine commentators really do know that there is more to wine-quality assessment than simply giving the wine a number. Indeed, Robert Parker, who was heavily involved in popularizing the scoring of wine, actually did note, way back in 1989 in the Wine Times: “[My] scoring system was always meant to be an accessory to the written reviews, tasting notes. That’s why I use sentences and try and make it interesting ... There’s a certain segment of my readers who only look at numbers, but I think it is a much smaller segment than most wine writers would like to believe.” I am not quite so sure about that last bit, which is why I have written this blog post.

Alternatively, James Halliday, from Australia, once commented: “Points are as subjective as the words in the tasting notes, but are a separate way of expressing the taster’s opinion, to be assimilated along with the description of the wine in the context of the particular tasting. All this may frustrate some consumers, but the ultimate reality is that Australia can never make Champagne, a Burgundy or a Bordeaux, so direct points comparison is fraught with contradictions and qualifications.”

We should not, of course, conclude from this that points are pointless. But we might conclude that the sometimes-heard argument that numbers are more precise than words is not really relevant in the case of assessments of wine quality. There is more to wine than can be expressed by a number; and, moreover, there are other ways to express quality (see: If not scores or words to describe wine quality, then what?).

By the way, how many of you know that Jancis Robinson has a degree in mathematics (and philosophy) from the University of Oxford? More to the point, how many wine scores have you ever seen from her? This should make you pause, and think.

Monday, December 6, 2021

The pandemic will not be over for a while yet

Pandemics

A pandemic is an epidemic that affects whole continents. An epidemic, in turn, involves the wide spreading of some disease-causing pathogen (eg. virus, bacterium, fungus, apicomplexan). In each epidemic, the pathogen spreads easily among a large number of people (or other animals, and plants), causing them to develop a particular disease; and it may well cause a considerable number of deaths.

Medically, "situation normal" for diseases involves elderly people, because they can easily succumb to many diseases (ie. their personal immune system has become weakened). For example, every year, elderly people are encouraged to take a "flu shot" (a vaccine; see below) to help them cope with whatever the current widespread influenza virus happens to be. An epidemic (which is unusual, by comparison) therefore occurs when younger people are affected, as well as the elderly.

The current pandemic thus initially surprised the medical people (and the government authorities) when it started out principally affecting older people. Epidemics do not normally start like that, being common principally among older people. Sadly, a lot of old people died early on, before the authorities realized that this group needed special protection.

They are not the only risk group, however. Males are much more likely to get sick (and die) than are females, for example, along with people who have high blood pressure, or Type-II diabetes. Have a guess who is old and male, with family-inherited high blood pressure and Type-II diabetes? Sometimes, I think that it is not safe for me to leave the house!

SARS versus Covid

SARS-CoV-2 is a virus, a foreign piece of genome that can get inside living organisms (the hosts), and proliferate there. Covid-19 is a disease, which is the host body's reaction to that foreign genome. I would say that confounding these two things is the single most common mistake made by the media. They say that something, like a mouse or a hippo is, "infected with covid" when they mean "infected with SARS". If the infected mouse does not react to the virus, then it does not have Covid-19, even though it has (and can transmit) the virus. This confusion cannot help the general public to understand what is going on.

So, Covid is you, SARS is the virus — you get infected by the virus, and react by developing the disease. This distinction is vital to how we deal with the current pandemic (as discussed below). Some people react so well that they don't even notice that they are infected with the virus, while others get severe cold-like symptoms; and many react so badly that they die (officially, 5.3 million, so far, which is 20% of the number of officially reported infections).

Our immune system is our body's defense against foreign genomes (or other bodies). Our own body can heal a cut or scratch, but in addition the immune system deals with anything foreign that enters through the damaged area (that is what the pus is doing, for example). In particular, your immune system will usually remember how to deal with every pathogen that your body has ever encountered — every cold, every bout of flu, and every vaccination. Some immune systems do better than others, though, which is why we all differ in how we react to disease-causing organisms. Importantly, your immune system may not be able to deal with any of the pathogens that you have not yet encountered.

Viruses cannot live outside the host, which makes them different from all other pathogens. Bacteria have a cell wall, for example, and can maintain a separate existence. However, a virus is not a cell — that is why we often call them "particles", not cells. They do not last all that long in the open air.

This means that a virus needs to get from one person to another pretty quickly. The easier they can do this, the more contagious they can be. Moreover, killing the host is a pretty bad move, because the virus dies along with the host. That is, the virus needs to keep the host alive, so that the host can continue to spread the virus particles to new hosts.

In this sense, an infected person who is not sick is the worst possible scenario for us, but the best one for the virus. During the course of an epidemic, new virus genomes continually appear, due to genetic mutations (viruses mutate easily) — in the current case, these variants have been called Delta and Omicron, and so on. Through time, these new variants are usually much more contagious than their predecessors (they spread more easily), but they are less likely to be deadly. So far, this looks to be true of the new Omicron variant: it is highly contagious but seems to cause milder symptoms — this is exactly what we would expect, based on previous pandemics.

As another example, the immediate predecessor to SARS-CoV-2 was called MERS. It was far more deadly than its own predecessor, called SARS. As a result, MERS did not spread beyond the Middle East, where it arose — it killed people before they could spread the virus particles. It thus did not cause a pandemic, and was thereby safe for the rest of us. SARS-CoV-2 is another matter entirely, compared to both SARS and MERS. Without action from us, the only way this pandemic is likely to end is to wait (who knows how long) for a variant to become predominant that does not kill at all.

Incidentally, the coronaviruses, as a group, are so problematic because they normally do not kill humans. Indeed, they are one of the causes of the common cold — about 15% of all colds are caused by coronaviruses, and so most us have been infected by one at some time or another. Colds are so common because the virus particles spread easily, but do not kill their host — the host just soldiers on, spreading the particles to new hosts. So, in one sense, SARS-CoV-2 is simply a mutant cold virus that can kill. (Note: there is no known cure for a cold — we solely treat the symptoms.)

Vaccines

Since your immune system may not be able to deal with any of the pathogens that you have not yet encountered, we usually need to do something about any new epidemic. That is where vaccination comes in — we give your body some sort of (safe) experience of the new pathogen, so that your own immune system can work out what to do about it. This vaccine* will protect you when the real thing turns up.

Think of it like a seat-belt in a car. The seat-belt does not prevent you from having an accident, but it can help tremendously with your reaction to the accident. Indeed, the seat-belt can keep you alive; and all cars are now fitted with them, by law.

Well, a vaccine is a seat-belt, nothing more. It cannot stop you from catching a virus, but it can help enormously with your reaction to the virus infection, preventing development of the disease. So, yes, it is perfectly normal for vaccinated people to get infected, although we would prefer that this does not happen. However, the vaccine should stop people from dying in response to that infection.

So, when driving a car, you still have to drive safely, even though you are wearing a seat-belt. Similarly, you still have to keep away from infected people (ie. socially distance), even though you are vaccinated. This virus is spread by aerosols, which are the finest suspensions in the air — distance is your best way not to breathe in infected air from another person. Remember, though, just like a seat-belt, a vaccine cannot guarantee to save you, although it will greatly improve your chances.

So, can you all now see why we are still having global problems? People are sick and tired of the whole affair, and want it to be over. So, they get vaccinated, and immediately try to return to a "normal" life. That is like buckling up a seat-belt and then driving without regard for the road rules. The best approach is to drive safely, even if you have filled your car with safety devices.

This is why the pandemic is not going away any time soon. You are still being subjected to infected people in your vicinity, even when you are vaccinated. The vaccine will help with your immune reaction, but not with your original action in contacting the infected person in the first place. While-ever there are infected, or potentially infectious, people on this planet, the pandemic cannot become history.

Protection thus ultimately comes from group behavior, not from the behavior of individuals — we all need to be uninfected, not just some of us (medically, this is called "herd immunity"). Your biggest danger is not the virus itself, but the people who refuse to protect themselves from it, and can thus infect you, whether they intend to or not — the virus cannot harm you if there is no-one to give it to you.

In the meantime, my wife and I still behave like we are elderly people in a pandemic that can kill us, even though we are both fully vaccinated. We still keep as far from other people as we reasonably can — for example, we visit the supermarket when it is not busy, and we prefer to attend outdoor events (like Christmas markets, at the moment).

The worst pandemic in history

Many people consider the Black Death to have been pretty bad, because a larger percentage of the known world population died, compared to any other pandemic. This was a plague epidemic, which is caused by a particular bacterium (not a virus). There have been plenty of plague epidemics in history. Indeed, the Bible is full of them — many of the catastrophes attributed to God's displeasure are now recognizable as having been plague epidemics.

However, the pandemic that killed the largest number of people occurred only a century ago, not a millennium. This was another viral epidemic, caused by an influenza virus. These are pretty common, too, often under the name "swine flu" or "bird flu". They have these names because we often share so-called H1N1 influenza viruses with pigs and birds (apparently we have a lot of physiological similarity to them!). The most recent such pandemics were in 2009, and before that in 1977. (Aside: One reason that we have dogs and cats as domestic animals is because we don't share pathogens with them — you certainly won't catch Covid-19 from them, or give it to them.)

So, one common scenario is that migrating birds spread the influenza viruses to where there are pig farms. The viruses infect the pigs; and new viral genetic variants then arise in those pigs. These new variants then get into the farmers, and they spread from there to the rest of us. The problem is that even if the new viruses do not kill the pigs, these new variants can kill us.

So, where would we look for a lot of pig farms under a major bird migration route? If I was in the USA, I would look in Kansas. So, it is of no surprise that the so-called Spanish Flu of 1918 was first detected on Kansas pig farms. (The mis-naming apparently comes from official attempts at a cover-up, trying to maintain morale in Europe at the end of World War I — the Spanish were the main ones prepared to report the epidemic, and the label has stuck.)

In Kansas, the virus spread to the nearby troop encampments, where the men were to be sent to Europe. Well, the rest follows like night follows day. A set of trans-Atlantic troop ships is an ideal place to spread a flu virus. When the infected troops turned up in Europe, what did they find? A set of field hospitals with half-dead soldiers, which is another ideal location for spread; along with a set of towns bombed to pieces, so that the homeless people were all jammed into church halls, which is another ideal location. The official figures indicate that more people died in that pandemic than died in the actual War itself (both military and civilian combined).

So, thank your lucky stars that the current pandemic has been nothing like that one. We are all having a tough time, sure, but almost all of us will live through it, this time (and without the red crosses that marked the doors housing plague victims during the Black Death). So, buckle-up and drive safely — get vaccinated, so our societies can get to herd immunity sooner rather than later. You were vaccinated against all sorts of childhood diseases, and it did you a power of good (no more polio, tetanus, hepatitis, rubella, measles, whooping cough, mumps, diphtheria, chicken pox ...) .

* Vaccination is one of the greatest contributions ever made to medicine, and it was made by uneducated women (anti-vaxxers take note). The "old wives tale" among cow maids (tending the cows on their summer pastures) was that they did not contract chicken pox because they got cow pox, instead. That is, catching the pox virus that we share with cows (which is not deadly) prevented them from getting ill from the pox virus that we share with chickens (which is deadly, and used to be one of the most common causes of child mortality). You can imagine how the (male, highly educated) medical people responded to this claim. Still, one of them finally decided to check it out; and (blow me down) the women were right. That is why we call it vaccination ("vacca" is the Latin word for "cow") — it's the cow treatment.

Monday, November 29, 2021

What is an old vine?

However, oldness is a relative thing. In the USA “old vine” seems to mean anything more than 30 years old. In Australia, they don't call them “old” unless they come from the 1800s (the oldest recorded ones seem to have been planted before 1850). If I look out my back window, I can see a dozen oak trees that seem to be a couple of hundred years old, so even 1850 may be a bit young, for a plant.

If I look out my front window, I can see across the field to the farmhouse that used to own the land on which my house stands — it appears on a map dated 1699. My house, on the other hand, dates from 1990. If I look out my side window, I can see across the creek to the church, which is dated c. 1400 AD. In front of it stands the original small chapel, which is dated c. 1200 AD.

This is not an exercise in one-up-manship, but is intended simply to emphasize that oldness is relative, not absolute. A medieval church is obviously older than almost all plants. We therefore need to compare plants with plants; and also we should really use the word “older” instead of “old”.

There is, as far as I know, no official definition of “old vines”, or “vieilles vignes” if you prefer French. As far as individual plants are concerned, you can read about the oldest known grapevines in Wikipedia; but we are talking here about whole vineyards, producing commercial wines.

Let’s start with what are believed to be the oldest vineyards, so that we have a baseline. They are all in Australia, which has the advantage of isolation in order to preserve much of its heritage.

The Freedom Shiraz vineyard, at Langmeil in the Barossa Valley (South Australia), was apparently planted in 1843, by Christian Auricht. His original plantings survive today (c. 1 acre), although the vineyard now combines younger vines with the originals. Similarly, the Turkey Flat Shiraz vineyard, also in the Barossa Valley, was planted in 1847, by Johann Frederick August Fiedler. These seem to be the oldest vines whose age has been authenticated; but today they are also a combination of younger vines with the originals.

The oldest vineyard that is claimed to consist entirely of original vines is another Shiraz one, but this time from the Goulburn Valley (Victoria). The Tahbilk Shiraz vineyard was established in 1860, with Ludovic Marie as vigneron. It has had a checkered history, but the original cellars and vineyard from 1860 are still in use.* Incidentally, Tahbilk also claims to have the largest single holding of Marsanne grapevines in the world (100 acres), originally also planted in 1860, although the current vines date from 1927.

There are apparently a couple of other vineyards in the world, some of whose vines date back to this same period. Jancis Robinson's Old Vine Register was originally compiled by Tamlyn Currin in 2010, and it has been updated occasionally since then (last updated 27 Nov 2019). It lists two such vineyards:

- Henri Marionnet, Domaine de la Charmoise (Touraine, Loire, France) — c.1850

- Hess Family, Colomé (Calchaqui Valley, Salta, Argentina) — 1854

However, most of the other vineyards that have been formally recorded date from the 1880s onward.

For example, California's Historic Vineyard Society has a Registry of Heritage Vineyards, based on three criteria:

- A currently producing California wine vineyard

- Original planting date at least 50 years ago

- At least 1/3 of existing producing vines can be traced back to the original planting date.

- Saucelito Canyon (San Luis Obispo) — 1880?

- Cazas Vineyard (Temecula Valley) — 1882

- Old Hill Ranch (Sonoma Valley) — 1885

- Bechthold (Lodi) — 1886

- Monte Rosso (Moon Mountain) — 1886

- Dona Marcelinas (Santa Rita Hills) — 1887?

- Bedrock (Sonoma Valley) — 1888

- Martinelli Road / Banfield) (Russian River Valley) — 1880s

- Old Crane / G.B. Crane Vineyard (St. Helena) — 1880s

- Picchetti (Santa Cruz Mountains) — 1880s

There is also a South Africa Old Vine Project, which has a list of the 30 Oldest Old Vine Blocks in South Africa. The oldest three date from 1900 (in Wellington, Swartland, and Breedekloof).

Given the number of older vines in the Barossa Valley, it should come as no surprise that there has been one attempt to formalize a few definitions of oldness, in the form of the Barossa Old Vine Charter (2009):

- Barossa Old Vine — at least 35 years of age

- Barossa Survivor Vine — at least 70 years of age

- Barossa Centenarian Vine — at least 100 years of age

- Barossa Ancestor Vine — at least 125 years of age

- Cirillo Estate Wines (Barossa Valley) — 1850

- Old Garden Vineyard (Barossa Valley) — 1853

- Torbreck Russell Vineyard (Barossa Valley) — 1857

- Tyrrell’s Wines (Hunter Valley) Stevens Vineyard Old Patch — 1867

- Bests's Wines (Great Western) — 1868

- Tyrrell’s Wines (Hunter Valley) 4 Acres Vineyard — 1879

- Mount Pleasant (Hunter Valley) Old Hill Vineyard — 1880

* The winery is definitely worth a visit. I still remember a visit at the beginning of a cold winter day, in which I literally had to cup the tasting glass in my hand for a minute, to warm it enough to smell its contents.

Monday, November 22, 2021

The world’s best vineyard experiences?

Anyway, given this philosophy, it is hardly surprising that carefully prepared vineyard and winery experiences for tourists have come to the fore in recent years. Some of these are described in: Out-of-the-box winery experiences help wineries reach new customers: “From helicopter and horseback to Peloton rides, brand awareness and customer engagement are the goal — not ROI.”. This seems quite unlike the old days, where the main idea was to taste the wines.

In this regard, The World’s Best Vineyards Academy tries, each year, to compile a list of the world’s best vineyard experiences. It works like this:

The Academy comprises nearly 600 leading wine aficionados, sommeliers, and luxury travel correspondents from across the globe. Each has been selected for their expert opinion of the international wine and wine tourism scene. [Each year,] they each vote for 7 vineyards in preferential order. There is no pre-determined checklist of criteria, except that the vineyard must be open to the general public. Each vote is a nomination for a vineyard experience that they deem to be the best in the world. The experience will take in all things connected with the visit — the tour, tasting, ambiance, wine, food, staff, view, value for money, reputation, accessibility. It’s everything that makes a vineyard visit a valuable and rewarding experience for visitors, and makes guests want to return or recommend a visit to their friends.Sounds reasonable, at least to me. Three ranked lists have been released to date: 2019 (a list of 50 vineyards), 2020 (also 50 vineyards), and 2021 (a list of 100 vineyards). Obviously, the thing for us to do in this blog is to compile the three lists, to compare and contrast them. So, I downloaded all three of them, and then created a combined ranked listing, which I report on here.

There are 112 vineyards listed at least once, but only 31 of them appeared in all three lists. This is somewhat less than 30%, which seems to imply that vineyard experiences are not all that repeatable from year to year.

There are 26 vineyards that appeared in two of the lists; and 55 that appeared only once. That is, c.50% of the vineyards had only one good showing. Of them, the unexpected ones are from the 2019 list, where: R. López de Heredia Viña Tondonia (Rioja, Spain) came in 3rd, but was never listed again; and Weingut Tement (Styria, Austria) came 15th, while suffering a similar fate. These are serious falls from grace.

For those vineyards that appeared in two out of the three lists, there were 2 that appeared in the first two lists but not the third (ie. they faded from view through time), and 16 that appeared in the second and third lists but not the first (ie. they rose to prominence). What is odd, though, is that there are also 8 vineyards that appeared in the first and last lists (ie. 2019 & 2021) but not the middle one (2020).

This latter point does make me wonder a bit about the choices by the experts, and how much of a lottery the results might be. After all, it is not like all of these vineyards were borderline in the lists. For example, Bodega Colomé (Salta, Argentina) was listed 25th (2019) and 35th (2021), Viña Santa Rita (Maipo Valley, Chile) was 26th and 28th, Creation Wines (Walker Bay, South Africa) was 45th and 10th, and El Enemigo Wines (Mendoz, Argentina) was 41st and 24th. It is hard to believe that they all went off the boil for a year in the middle.

Anyway, we do have 31 vineyards that were consistent across the three lists. These are listed below, in the order of their average rank across the lists.

Zuccardi Valle de Uco (Mendoza, Argentina) was listed at the top of all three lists (pictured below), while Bodega Garzón (Maldonado, Uruguay) was 2nd, 2nd and 4th (pictured above). So, a vinous trip to South America is clearly called for. In addition, in the top 7 were Montes (Colchagua Valley, Chile), Catena Zapata (Mendoza, Argentina) and Viña VIK (Cachapoal Valley, Chile), thus providing three more reasons to buy that plane ticket. This may explain the recent interest in The new cult vineyards of South America.

Overall, there were 7 (of the 31) vineyards from Chile, 3 from each of Argentina and France, and two from each of Australia, Germany, New Zealand, Spain, Uruguay and the USA. There was one vineyard each for Austria, Greece, Italy, Lebanon, Portugal, and South Africa. Fortunately, that does cover the major wine-producing countries, so, no matter where you are there is an experience nearby.

In one sense, to me this is all beside the point. The best wine experience, it seems to me, is to sit down with the actual winemaker in a relaxed manner for a chat about the wines: all of the rest makes it seem more like Disneyland than a genuine life experience.

In this sense, one of my personal favorite stories involves Llew Knight, of Granite Hills winery in the Macedon region of Australia. This was a long time ago, when both of us were much younger. His parents were looking after the tasting room when I came in. However, when they realized that I was not just a passing tourist, but had specifically targeted them, they called their son in to take over. He was clearly watching the football at the time, but came out anyway, for which I have always been grateful. This sort of simple country friendliness is one of the things I value most.

To bore you with a second story, I once visited Talijancich Wines, of the Swan Valley in Western Australia (back in the 1980s). It had until recently been called Peter’s Wines, and a colleague of mine (named Peter Valder) liked to serve his dinner guests with a label that matched his own name; so he asked me to get a supply for him, since I was in the area. I knew nothing about the place before arriving. However, I still remember having my socks knocked off by their fortified wine, which had more flavors competing for attention than anything else I have ever tasted. They explained to me that it was simply a blend of all of their wines that had ever won an award. This sort of pleasant surprise is my sort of experience.

This list covers the 31 vineyards that made it onto all three lists of the World’s Best Vineyards (2019–2021). They are listed in order of their average rank.

|

Winery Zuccardi Valle de Uco Bodega Garzón Montes Bodegas de los Herederos del Marqués de Riscal Catena Zapata Quinta do Crasto Viña VIK Antinori nel Chianti Classico (Marchesi Antinori) Château Smith Haut Lafitte Rippon Craggy Range Domäne Wachau Château Margaux Clos Apalta Robert Mondavi Winery Schloss Johannisberg Weingut Dr Loosen Penfolds Magill Estate Delaire Graff Estate Opus One Winery d’Arenberg Familia Torres — Pacs del Penedès Bodegas RE Château Mouton Rothschild Viña Casas del Bosque Viu Manent Bodegas Salentein Bodega Bouza Château Héritage Viña Errázuriz Domaine Sigalas |

Region Mendoza Maldonado Colchagua Valley Rioja Mendoza Douro Valley Cachapoal Valley Tuscany Bordeaux Central Otago Hawke’s Bay Wachau Bordeaux Colchagua Valley Napa Valley Rheingau Mosel South Australia Stellenbosch Napa Valley South Australia Catalonia Casablanca Valley Bordeaux Casablanca Valley Colchagua Valley Mendoza Montevideo Bekaa Valley Aconcagua Valley Santorini |

Country Argentina Uruguay Chile Spain Argentina Portugal Chile Italy France New Zealand New Zealand Austria France Chile United States Germany Germany Australia South Africa United States Australia Spain Chile France Chile Chile Argentina Uruguay Lebanon Chile Greece |

Monday, November 15, 2021

Are alcohol-free wines drinkable (by wine drinkers)?

This does not, of course, mean that such wines are taking over the industry, as the segment apparently still accounts for less than 1% of the market (Non-alcoholic beer, wine and drink sales soar as quality improves). However, this does mean that the current state of the art is worth looking at.

Low-alcohol wines seem to include everything that is below the common alcohol concentration for any given wine type — eg. <11% ABV for reds and <10% for whites. This seems more like “lower” rather than “low”. It is often achieved, in practice, by choosing grapes from varieties that naturally produce wines with the desired alcohol level (eg. Gamay, Riesling, Moscato, or the Vinho Verde varieties such as Alvarinho).

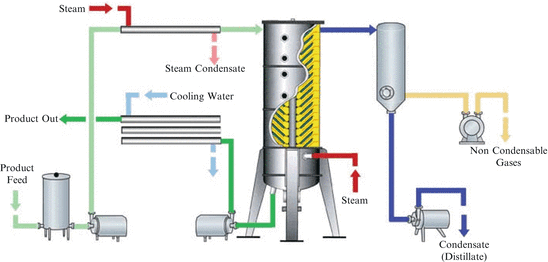

Alcohol-free wines are another thing entirely. Here, we need to remove the alcohol from the fermented grape-juice, getting it to <1% ABV — without impairing the expected wine sensory perception, including mouth-feel (texture), balance (acidity), and typicity (aromas and tastes).

On the face of it, this seems to be a hopeless task. What we do first is convert the grape sugar into alcohol (by fermentation); and then we try to remove that alcohol from the resulting juice (eg. by spinning cone technology, or by reverse osmosis). It seems to me that this is likely to leave us with strange-tasting sugar-free grape juice.

Apparently I am not the only one to think this (What are the opportunities for the no- low-alcohol wine category?): “The consumer data collected by Wine Intelligence over the past 5 years has been telling a similar story: no- and low-alcohol wine is a good idea in theory, but consumers are often disappointed by the taste profile of products in these categories”.

So, some manufacturers subsequently add a bit of grape concentrate at the end (eg. 5%), in an attempt to improve matters; and some makers even add a bit of flavoring, and even gum arabic for texture. All of these things can be produced organically, of course, so that the resulting alcohol-free wine can legitimately be labeled “organic”. Mind you, I have noticed that several wineries do not actually mention their alcohol-free wines on their websites!

However, would a wine drinker want to drink the result? This is a question I asked myself recently; and I decided to find out. [Updated: 18-Nov-21.]

To find out empirically, I bought most of the wines available in my local Swedish liquor chain (Systembolaget), as well as my local supermarket (ICA), which cover a range of styles, and a range of prices (40 unique brands). I expect these wines to be representative of those available elsewhere, and many of them are also available in other countries. None of them are actually made here in Sweden, although they are quite popular here — for example, the data on Exports of Australian reduced alcohol wine by market show that 47% of their total goes to Sweden.

My long-suffering wife and I then drank all of them, one per day. Here, I report on the results, which are summarized in the table at the bottom of this post. Our thoughts focus on the taste, because without alcohol there is not much aroma. Interestingly, the amount of residual alcohol (0%—0.5%) seemed to make no difference to the wines.

Starting with the reds (9 wines), all of them tasted awful, although the Domaine de la Prade is drinkable. They all tend to taste the same, irrespective of grape or geographic origin — that is, they taste like grape juice, not wine. The producers describe this as “bursting with bright red fruits”! It's like discovering that all of red-wine diversity has been reduced to Beaujolais Nouveau. There is nothing wrong with Beaujolais Nouveau, but there is more to red wine than solely this. Interestingly, like Beaujolais Nouveau, the wines do taste better chilled.

The whites (9 wines) are definitely a step up, as they can handle the grapey fruitiness, by being chilled. However, they also tend all to taste the same, irrespective of grape or origin — they do not taste anything like the nominated grape, unlike wine. This is not to say that they are not a refreshing beverage, of the simple and fruity type (although the Santa Monica was a bit acidic).

The rosé drinks (5 wines) are very similar to the whites, and thus similar comments apply. In this case, for the cheap alcoholic versions, no-one expects rosé to taste like any particular grape; so, the lack of diversity is no surprise. You would not, however, mistake any of these for a real rosé.

This brings us to the sparkling versions (17 wines). These are far and away the best of the segment. The bubbles can handle the grape fruitiness, by cutting through it. They are all carbonated, of course, and the cheapest ones go flat fast. However, as a refreshing aperitif, or even with a meal, most of these are quite acceptable. In terms of flavors, they tend to taste more like pear or apple than anything else. However, the top-7 in terms of price were a step above this, and actually tasted a bit more like wine.

I am not the first to note that the sparklings do better than the others ( “the carbonic acid provides freshness and mouthfeel”). Indeed, it is reported that Brut sparkling wines demand to dominate, yielding a third of the global revenue share.

Overall, I remain unimpressed. Alcohol-free wine may be good for your health, but that does not make it is good for your taste buds. It has been reported that quality is increasing (Pleasure without remorse: the best non-alcoholic wines; Best non-alcoholic wine 2021), and I hope so.

However, I would probably much prefer just to drink fresh fruit juice, rather than trying to consume doubly-processed grape juice. After all, making wine and then de-alcoholizing it is more complicated than just making the wine in the first place, and yet most alcohol-free wine is less expensive than its alcohol-containing counterpart — that should give you a hint about what to expect in terms of quality.

To test the idea of preferring fruit juice, I also purchased two of the ones in wine bottles, available on the same shelves in the shops:

- Azienda Iris P.Lex Pure Sparkling Glera (Italy; $7.50) (carbonated grape juice)

- Le Petit Béret Organic Chardonnay (France; $10.25) (grape extract, grape juice, apple concentrate)

We tasted all of these wines so that you don’t have to. The best summary is indicated by my wife's expression of relief when she got a real wine with her dinner, after five evenings of drinking the de-alcoholized stuff (and several more nights afterwards). If I want grape juice, I will just buy unprocessed grape juice. If I want still wine, then in order to cut down on my alcohol intake I may be better off choosing ones that are naturally lower in alcohol (eg. Gamay, Alvarinho). However, the top-level sparkling wines would probably pass muster even with a (co-operative) wine-preferring guest.

|

Producer Reds Jacob’s Creek Carl Jung Les Grands Chais de France Enjoy Wine & Spirits Treasury Wine Estates Treasury Wine Estates Sommestad & Malmnäs Oddbird Edenvale Whites Carl Jung Henkell Freixenet Casa de la Ermita Miguel Torres Enjoy Wine & Spirits Treasury Wine Estates Jacob’s Creek Josef Leitz Edenvale Rosé Carl Jung Jacob’s Creek Reh Kendermann José Maria da Fonseca Josef Leitz Sparkling G. Patritti Henkell Freixenet Henkell Freixenet Les Grands Chais de France Treasury Wine Estates Treasury Wine Estates Arc-en-Ciel Enjoy Wine & Spirits Henkell Oddbird Pernod Ricard Domaine Wines GodDryck i Sverige GodDryck i Sverige Oddbird Oddbird GodDryck i Sverige |

Wine name UnVined red Carl Jung JP Chenet So Free Barrels and Drums Lindeman’s Rawson’s Retreat Cognato Domaine de la Prade Premium Reserve Carl Jung Chapel Hill Santa Monica Natureo Barrels and Drums Lindeman’s UnVined white Eins Zwei Zero white Carl Jung Rosé UnVined Rosé Black Tower Rosé Periquita Rosé Eins Zwei Zero Billabong Brut Chapel Hill Chapel Hill Rosé Nozeco Lindeman’s Rawson’s Retreat Rosé Mousseux Brut Barrels and Drums Mionetto 0.0% Spumante Campo Viejo Gran 0% Richard Juhlin Blanc de Blancs GodDryck No 1 Sparkling White GodDryck No 2 Sparkling Rosé Rosé Blanc de Blancs GodDryck No 1 Prestige Cuvée |

Grape(s) Shiraz Merlot Cabernet sauvignon + Syrah Merlot Cabernet sauvignon Cabernet sauvignon Cabernet sauvignon + Cinsault Merlot + Shiraz Pinot noir Chardonnay Chardonnay Viognier + Macabeo Muscat Chardonnay Semillon Chardonnay Mostly Riesling Riesling Pinot gris unspecified Shiraz Grenache + Tempranillo + Syrah Syrah Pinot noir unspecified unspecified unspecified unspecified Chardonnay + Pinot noir + Muscat Chardonnay + Pinot noir + Muscat Grenache Chardonnay Glera Glera Xarel-lo + Macabeo + Parellada Chardonnay Sémillon + Airén + Sauvignon blanc Cabernet sauvignon + C. franc + Merlot Chardonnay + Pinot noir Chardonnay Chardonnay + Sauvignon blanc |

Source South-eastern Australia Germany (Spain) France Germany (Spain?) South-eastern Australia South-eastern Australia South Africa France South-eastern Australia Germany (Spain) Hungary Spain Spain Germany (Spain?) South-eastern Australia South-eastern Australia Germany South-eastern Australia Germany (Spain) South-eastern Australia Germany (Spain) Portugal Germany South-eastern Australia Hungary Hungary France South-eastern Australia South-eastern Australia France Germany (Spain?) Italy Italy Spain France Spain + France France France France Spain + France |

Alcohol ABV 0.5% 0% 0.3% 0% 0% 0.5% 0.5% 0% 0.5% 0% 0% 0.5% 0% 0% 0% 0.5% 0% 0.5% 0% 0.5% 0% 0.5% 0% 0.3% 0% 0% 0.4% 0% 0.5% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0% 0.2% 0.2% 0% 0% 0% |

USD $4.50 $5.00 $4.50 $6.50 $6.50 $6.75 $8.00 $10.25 $11.50 $4.75 $4.75 $6.50 $6.50 $6.50 $6.50 $6.75 $8.00 $9.25 $4.75 $5.75 $5.75 $5.75 $8.00 $4.50 $5.00 $5.25 $5.75 $6.75 $7.00 $7.00 $7.00 $9.25 $9.25 $10.25 $10.25 $10.25 $10.25 $11.00 $11.00 $14.00 |

Monday, November 8, 2021

Unrecorded versus officially Recorded alcohol consumption

However, all of this ignores what is usually called the “unreported” or “unrecorded” consumption. This includes all sorts of alcohol, such as home-made fermented wine and beer, home-made distilled spirits (moonshine), smuggled alcohol, re-purposed alcohol (eg. originally intended for industrial or medical uses), surrogate alcohol (eg. ethanol), etc. What are we supposed to think regarding all of this? Doesn’t this also count as “alcohol consumption”?

Well, it turns out that the World Health Organization has had a go at trying to look into this topic. Their WHO Global Status Report on Alcohol and Health 2018 has data for both Recorded and Unrecorded alcohol consumption for each of 189 countries (or territories). You can also find the data tabulated on Wikipedia (List of countries by alcohol consumption per capita).

The data are 3-year averages for 2015–2017, based on persons 15 years and older. The Recorded alcohol “is alcohol consumed as a beverage that is recorded in official statistics, such as data on alcohol taxation or sales” (see the WHO Global Survey on Alcohol and Health), while the Unrecorded amount was mathematically modeled based on the data from several surveys, including expert judgements (see Appendix IV.1.2 of the WHO report). Both data are reported as pure alcohol consumption in liters per capita per year.

I have graphed the data in the following figure. Each point represents one country (or territory) in the WHO table, with the Recorded consumption horizontally and the Unrecorded consumption vertically. The so-called western countries are represented by the orange dots, with the remainder in blue.

The pink line represents the situation where the two types of consumption are equal — above the line, estimated Unrecorded consumption exceeds the officially Recorded consumption, and vice versa below the line.

Note, first, that there are not actually 189 dots visible in the graph, as some countries are superimposed, notably those with both consumptions reported as zero: Bangladesh, Kuwait, Libya, Mauritania, Somalia, and Yemen. Other countries have minuscule consumption, including: Afghanistan, Egypt, Iraq, Kiribati, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, and Syria. These are, as expected, all Moslem-dominated countries.

For the western countries (orange dots in the graph), Recorded consumption usually far exceeds Unrecorded consumption. For example, the countries at the bottom-right of the graph include (from the right); Estonia, Lithuania, Czechia, and Austria. However, there are five such countries where Unrecorded consumption exceeds 30% of the total consumption (the orange points towards the top of the graph): North Macedonia (43%), Greece (40%), the Ukraine (36%), Albania (33%) and Russia (31%). Conversely, those countries where Recorded consumption is less than 10% of the total consumption include: Austria (3.4%), Estonia (6.5%), Italy (6.6%), the Netherlands (7.4%), Australia (7.7%), Lithuania (8.0%), the United States (8.3%) and Belgium (8.8%).

The non-western country at the top-right of the graph is Nigeria, with the sixth biggest total consumption, but with 28% of this being Unrecorded. The countries on the left of the line (Unrecorded > Recorded) are (from top to bottom): Vietnam, Myanmar, Tajikistan, the Maldives, East Timor, and Nepal. Here, access to professionally produced drinks is apparently very limited.

Note that Haiti is on the bottom axis (zero Unrecorded consumption), and Bahrain is only just above that axis. Similarly, a few of countries are on the vertical axis (zero Recorded consumption), including: Comoros, Niger, Iran, Sudan, and Afghanistan.

I have included below a list of the countries, ranked in decreasing order of how far they are from equality of Recorded versus Unrecorded consumption. That is, a large positive number in the ranking means that Recorded >> Unrecorded, whereas a negative number indicates Unrecorded > Recorded.

If you would like to see some neat graphs and maps about recorded alcohol worldwide, then consult Our World in Data — Alcohol Consumption.

The saga of the iPad Mini, mentioned in my last post, has continued. In spite of being a recent device, it has an old version of iOS. This version cannot be updated wirelessly, according to the error message I get, when I try to update it. The message says that I must instead use iTunes on a Mac. However, my Mac Mini is old, and when I connect the iPad it tells me that the Mac does not have a version of iTunes that will allow me to do this. I tried to use my MacBook, which is more recent, but its OSX operating system no longer has a separate iTunes app. I eventually found an iMac with an intermediate version of OSX — old enough to still have iTunes but recent enough to allow me to connect the iPad. Why is modern computing like this?!?

The following list sorts the countries by the extent to which Recorded consumption exceeds Unrecorded consumption. At the top of the list are those countries that are furthest from the line of equality, to the right in the graph (Recorded > Unrecorded), while those countries at the bottom are those furthest from the line of equality, to the left in the graph (Unrecorded > Recorded). The numbers are simply the shortest distance from each graph point to the line.

|

Territory Estonia Lithuania Czechia Seychelles Austria France Moldova Bulgaria Germany Ireland Belgium Hungary Cook Islands Latvia Slovenia Slovakia Australia Poland United Kingdom Portugal Luxembourg Andorra Equatorial Guinea Croatia Saint Kitts and Nevis Switzerland Denmark Romania Saint Lucia Belarus United States South Korea Cyprus New Zealand Barbados Gabon Grenada Serbia Bahamas Antigua and Barbuda Canada Argentina Uruguay Netherlands Spain Malta Italy Chile Finland Iceland Trinidad and Tobago St Vincent & the Grenadines Nigeria Namibia Uganda Japan Haiti Panama Dominica Brazil Sweden Georgia Niue Norway South Africa Thailand Rwanda Belize Eswatini Montenegro Russia Dominican Republic China Cameroon Botswana Mongolia Paraguay Mexico Kazakhstan Guyana Peru Laos Angola Venezuela Suriname Cuba Colombia Tanzania São Tomé and Príncipe North Korea Bosnia and Herzegovina Costa Rica Albania Cape Verde Bolivia Philippines Nicaragua Ukraine Zimbabwe Jamaica Ecuador Greece Gambia Armenia Bahrain Kyrgyzstan Congo Honduras Burkina Faso El Salvador Singapore Israel Mauritius Turkmenistan North Macedonia Samoa Liberia Fiji Ivory Coast Sierra Leone Sri Lanka Nauru Lesotho Guinea-Bissau Zambia Tunisia Lebanon Micronesia Guatemala Tuvalu Burundi Qatar Turkey Solomon Islands Ghana Uzbekistan Tonga Vanuatu India Kenya Brunei United Arab Emirates Malawi Togo Cambodia Azerbaijan Djibouti Kiribati Mozambique Papua New Guinea Algeria Malaysia Benin Morocco Syria Central African Republic Ethiopia DR Congo Oman Jordan Egypt Iraq Yemen Bangladesh Kuwait Libya Mauritania Somalia Eritrea Mali Saudi Arabia Indonesia Bhutan Afghanistan Madagascar Chad Senegal Pakistan Niger Guinea Sudan Maldives Comoros Nepal East Timor Iran Tajikistan Myanmar Vietnam |

Distance 10.4 8.9 7.8 7.8 7.8 7.3 7.1 7.1 7.0 7.0 6.6 6.6 6.6 6.5 6.4 6.2 6.2 6.2 6.2 6.0 6.0 6.0 6.0 6.0 5.9 5.9 5.9 5.8 5.8 5.7 5.7 5.6 5.5 5.5 5.5 5.4 5.2 5.2 5.2 5.1 5.1 5.0 5.0 4.9 4.7 4.7 4.7 4.6 4.5 4.4 4.4 4.2 4.1 4.1 4.1 4.1 4.1 4.0 3.9 3.7 3.7 3.6 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.5 3.4 3.4 3.3 3.3 3.2 3.1 3.0 2.9 2.8 2.8 2.8 2.8 2.8 2.8 2.8 2.5 2.5 2.5 2.4 2.3 2.1 2.1 2.1 2.1 1.8 1.8 1.8 1.8 1.7 1.7 1.7 1.6 1.6 1.6 1.6 1.5 1.5 1.5 1.4 1.4 1.3 1.2 1.1 1.1 1.1 1.0 1.0 1.0 0.9 0.9 0.9 0.8 0.8 0.8 0.8 0.7 0.7 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.6 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.5 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.4 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.3 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.2 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.1 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 0.0 -0.1 -0.1 -0.1 -0.1 -0.1 -0.1 -0.1 -0.1 -0.2 -0.2 -0.2 -0.4 -0.4 -0.4 -0.5 -0.6 -0.6 -0.7 -1.0 -1.1 -1.6 |

Monday, November 1, 2021

Is the future of wine on the blockchain?

However, the world has changed just as much during the subsequent 30 years, in a way that has at least partly passed me by.* Yes, that is right — I do not have a Facebook, Twitter or Instagram account, and my mobile phone does little more than receive phone calls. I have, however, run two blogs (including this one), if that counts for anything.

The point here is that I do like to think about where things are heading, even if I do not necessarily like to follow along. One thing I sometimes contemplate is the application of modern technology to the wine industry. So, the future of wine production and sales is of interest.

However, the title of this post is somewhat of a pun, because what I am talking about in this particular case is (the future of) Wine Futures — the idea of paying for your wine now, after the grapes have been crushed, but before the wine has been matured and bottled, and then taking delivery of your possession at some time in the future. How will this century-old idea change in the modern world?

The idea of Futures is very straightforward. The winery gets its money up front, so that it can spend the money on finishing the current vintage, and starting the next one. This is quite an appealing idea if you happen to be in the agriculture business, with new expenses throughout the year but income only once per year. In return, the customer gets to pay the current price, rather than the future price, as the latter is expected to be much higher. This is quite an appealing idea if you happen to be the one forking out the money, where it is often difficult to balance income with expenditure. So, both parties avoid the use of banks (and bankers) in the transaction!

So, why aren't there more Futures markets in the wine industry? The most famous (and oldest) is the en primeur system in Bordeaux, although we are told that “the system is increasingly used for wines from other regions, notably Burgundy, California, the Rhone Valley, Italy and Port” (Wine futures and en primeur). I don’t know about “increasing”, because it has been tried in some other places without much success. However, given the limited quantities of some burgundies on release, for example, buying them via wine futures is sometimes the only route to ownership. So, the idea is clearly here to stay.

Mind you, pay now / receive later does not always benefit the buyer. The Wine Spectator (How (and why) to buy wine futures) notes an example of each possible outcome — some parts of the 2000 Bordeaux vintage are now valued at double or triple their release prices, while the all-time high en primeur prices of the 2010 Bordeaux vintage have not held up at all (current wines are now available for well below their release prices).

What has all of this got to do with the blockchain? Well, the latter is simply an electronic ledger, in which all changes can be made only in public (in computer terms, it is a “distributed ledger”). This is clearly a potential tool for Futures, which require both a certificate of authenticity and a certificate of ownership (of the wine). Indeed, the same thing can be said of all “fine wine” sales, especially on the secondary market. Fine wine is said to currently be a hot investment; and a standardized way of demonstrating authenticity and ownership clearly has a role to play. The blockchain seems to be a good candidate.

The blockchain was invented as part of the development of the first successful cryptocurrency (Bitcoin). However, its application extends far beyond cryptocurrencies, irrespective of your attitude towards such non-government coinage. An electronic ledger can be used anywhere that a ledger is required. For example, it can also be used for contracts, in which case a trustee is not needed (and it is thus called a “smart contract”), as well as supply-chain management, anti-counterfeiting, etc. These days, companies offering blockchain services are proliferating.

An important distinction is that a cryptocurrency is a Fungible Token, which means that one coin can be exchanged for any other coin of the same type — each entry in the ledger refers to one of a large set of interchangeable items. A Non Fungible Token (NFT), on the other hand, is absolutely unique — each entry in the ledger refers to one thing and one thing only (ie. the tokens are non-interchangeable). NFTs are therefore what we are interested in for investments (whether it be in art, or land, or wine), or any other sort of financial service.

So, using NFTS on a blockchain would be one way to bring the Futures (en primeur) system into the 21st century.

But who would be using it? Given that the Futures approach is not usually used by ordinary wine drinkers, the potential market is presumably investors, and the rich in general, as well as the wine trade, in the broadest sense. In this regard, it is important to note that an electronic ledger details the entire history of the NFT in a verified and public manner; and it can contain whatever information is desired, in this case including, but not limited to, things like grape provenance and wine storage conditions.

There is at least one old-style example of using the Futures approach for individual wines for the general public, as well as the trade. Way back in 1977, the Saltram winery (in the Barossa Valley, Australia) decided not to fund the 1978 vintage, due to a fruit surplus. The winemaker at the time, Peter Lehmann, then literally became legendary, by deciding that this was no way to treat the grape-growers, all of whom he knew personally. So, he took out a bank loan, assembled the necessary equipment, and built a small winery to process their grapes. The first wine, in 1980, was called The Futures, because it was marketed on a “pay now and pick it up after two years in the cellar” arrangement, which was literally the only way it could ever work. When the money started coming in, naturally Peter made sure to pay the growers first. The high quality of this wine, incidentally, marked the beginning of the current resurgence of the Barossa Valley as a premier wine-making district.

So, there are good precedents here. The way to find out how this works in the 21st century, of course, is to try it, by releasing some wine using NFTs. It should therefore come as no surprise that this is, indeed, happening. A short while ago, a PR release appeared noting that the entire Neldner Road (Barossa Valley) 2021 vintage wines are to be sold by NFTs (Neldner Road winemaker Dave Powell’s “vintage of the century” to be sold by NFT). You can read a bit about the wines on the OpeanSea NFT website. This seems to be a world first; and I will be interested to see how it goes.

Mind you, this is not going to be cheap. Dave Powell, the winemaker, used to run Torbreck wines, and their prices were way out of my league. The current Powell & Son (now Neldner Road) wines are not much better, at $US 100-500 per bottle. If you want to buy the entire 2021 vintage, which you technically can do by purchasing a single NFT (rather than a set of NFTs), you will thus need the upper side of $US 9 million. [Update: you can now read more here: Aussie winemaker pivots from China to crypto] [Later update: other wine NFTs have started appearing; Luxury vintage wine barrel to be sold as NFT]

Finally, what are the currently known downsides of an NFT? The main criticism has been the energy cost of the computing needed for validating blockchain transactions, so that they have a high carbon footprint. This is not a trivial issue, if the blockchain is to be a widespread part of the future.

I wrote this post at least partly to prove to myself that I am not such an old fuddy-duddy as I sometimes think.

* I am currently trying to set up a new iPad Mini, which is now such an automated process that it is impossible to sort it out the problem, when things are not happening the way the description says they should. I cannot set it up from my old iPad, because I was never given the option, and the messages say that I cannot restore from the old iCloud backup, nor update the iOS wirelessly. I am seriously considering putting the thing back in its box, and continuing to use the old one until it collapses completely. Thanks Apple!